Clarence’s painting and drawing was not limited to his water colours of plants. He sketched landscapes, architectural detail, and other subjects especially when he was walking or travelling. Much of his illustration is enhanced into patterns, such as the repetitive use of the stem of a flower and its blossom to create a frame for a page in one of the visitors’ books or other vellum albums. He decorated the whole of the interior of the Casa Fontanalba in these floral designed and the umbrella pots of the Museo Bicknell (image left). His proverbs in Esperanto are most often illuminated with the same floral surrounds.

Clarence’s painting and drawing was not limited to his water colours of plants. He sketched landscapes, architectural detail, and other subjects especially when he was walking or travelling. Much of his illustration is enhanced into patterns, such as the repetitive use of the stem of a flower and its blossom to create a frame for a page in one of the visitors’ books or other vellum albums. He decorated the whole of the interior of the Casa Fontanalba in these floral designed and the umbrella pots of the Museo Bicknell (image left). His proverbs in Esperanto are most often illuminated with the same floral surrounds.

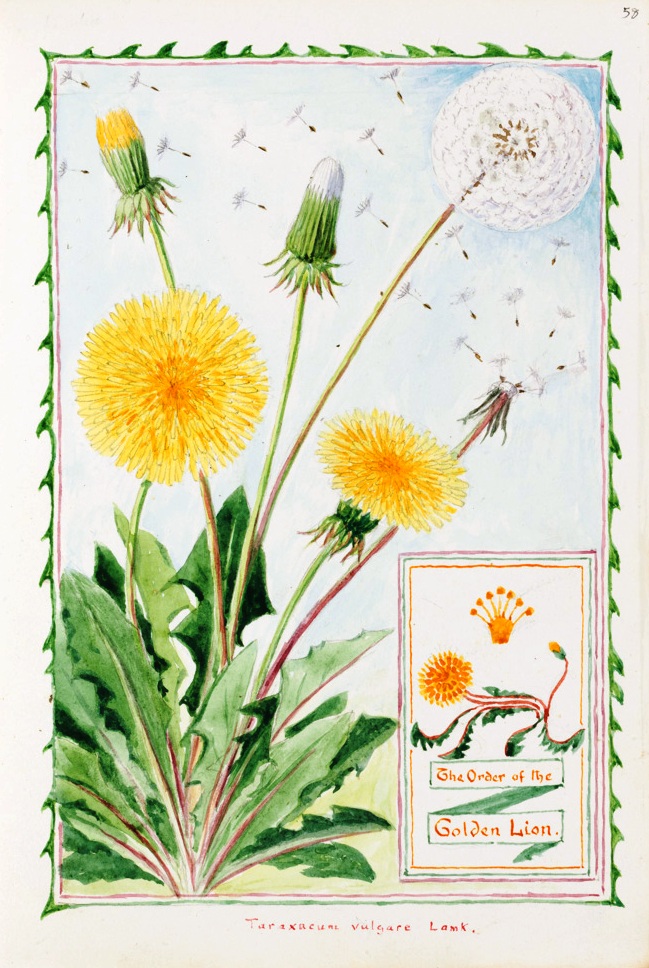

One of Clarence’s favorite flowers was the dandelion. This repetitive image (right) is from the Book of Visitors to the Casa Fontanalba in Esperanto.

In these ways one can consider Clarence a master of “arts and crafts”. Certainly, the Arts and Crafts movement flourished between 1860 and 1910, the period of Clarence’s greatest output, and he cannot have avoided influence from some of his peers. For example the movement was inspired by the writings of John Ruskin (1819–1900), among others, the same Ruskin who was a friend of Clarence’s father and a frequent guest at the family home in Herne Hill. It is likely that Clarence knew from the world around him that there was value in painted creativity other than just landscapes and portraits on canvas.

It is our intention at the Clarence Bicknell Association to invite a friendly expert in the Arts and Crafts world to assess Clarence’s contribution to the movement and or the creation by him of a new style. If you are that person or know of one do please contact us at info@clarencebicknell.com.

Marcus Bicknell,