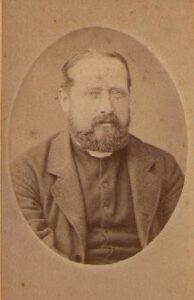

Like many a younger son of a moneyed 19th-century family, Clarence Bicknell went into the Church. This was a matter of genuine and felt devotion. At Cambridge University he was much influenced by an enthusiastic group of young churchmen. Soon after he had graduated in 1865, his 23rd year, he took orders in the Church of England, forsaking mathematics and the Unitarianism of his father and grandfather. For some years he was curate at Walworth, a tough parish in the slums of south London which supported the Order of St Augustine. This was a passionate, ritualistic community within the Anglican Church, mysteriously linked with Rome. Here he lived a simple life, devoting himself and much of his income to the poorest people. This pattern of simplicity, generosity and service was to be with him for life. He left Walworth and joined some of his Cambridge friends in the Brotherhood of the Holy Spirit in the village of Stoke-by-Tern in Shropshire. There he lived in a “high church” community devoted to the mission of preaching (see research paper by Valerie Browne Lester references at the bottom of this page).

After ten years he began to have serious religious doubts, and decided to avail himself of his inherited private means to see the world. Among the many places which he was able to visit in the late 1870s were Ceylon, Morocco and Majorca. Coincidentally or not, the Brotherhood of the Holy Spirit closed in 1879.

The year 1878 saw Bicknell arriving in Bordighera, as chaplain to the Anglican Church, at the invitation of the Fanshawe family. His diaries record his church duties, and the colleagues who assisted him when preaching a sermon. But his religious doubts were growing. He found the church too ritualistic, too dogmatic, too chauvinistic. Within a year he had resigned. He gave up active participation in church matters. He asked not to be referred to as “The Rev.” He ceased to wear a dog collar. He was later to say in a letter to a friend, “I fear I have become rather narrow about all church things, having become convinced that the churches do more harm than good & hinder human progress, & look upon the pope, the clergy & the doctrines as a fraud, though not an intentional one.” Practical works, like building a home for the aged of the commune, were more relevant. Ideals were better expressed in other kinds of communities, like the fraternity of Esperanto-speakers.

Bicknell’s idealism found practical expression in other ways. Though disenchanted with the church, Clarence had become enchanted by Bordighera, soon buying the Villa Rosa from Mrs. Fanshawe Walker and making it his home for the rest of his life. Bordighera had history (though much less than the neighbouring town of Ventimiglia), but it had no collected centre for its history or for a broader cultural life. So Bicknell built one, the Museo Bicknell. It was opened in 1888. For the architect of the Museo Bicknell we quote from MARVELS: The Life of Clarence Bicknell by Valerie Lester (2018)… Clarence “commissioned the British architect Clarence Tait, who elaborated on Clarence’s ideas, applied his knowledge to them, and drew up the design for the building”. On one of the fireplaces are the initial in crests of those who collaborated on the creation of the museum, CT, GG, FG and CB: Clarence Tait, Giovenale Gastaldi, Francesco Giovannelli and Clarence Bicknell. [MB March 2019]. Brick-built with a round-arched loggia, it has rather the feel of a Romanesque-revival church. Its main room is a big central chamber, with a stage at one end, and grand fireplaces on each long wall. These are decorated with patterns using plant motifs, in the distinctive style Bicknell was to use to perfection in the Casa Fontanalba. Re-fitted, the museum still plays that role. Its central room was the memorable venue for an anniversary conference in 1988, the exhibition for the 2018 centenary of his death and many other talks, lectures, art and music events.

Clarence continued his pastoral work in Bordighera and the environs, mostly in helping the poor, but little is written of the tangible aspects of this work. He was a pacifist and found the idea of a world war on his doorstep (the Italian army entrenched themselves firmly in the Alps above his house at Casterino and visited him there from time to time) difficult to countenance or to write about. In the years before the 1914-1918 war he threw what time he had left after his semi professional pursuits into Esperanto, which he considered a force for good and for world peace. He created an Esperanto group in Bordighera, photo above. In 1914, when World War I broke out, Clarence was at the Esperantist Congress in Paris looking after a party of blind Esperantists whom he safely escorted back to their homes in Italy

Clarence continued his pastoral work in Bordighera and the environs, mostly in helping the poor, but little is written of the tangible aspects of this work. He was a pacifist and found the idea of a world war on his doorstep (the Italian army entrenched themselves firmly in the Alps above his house at Casterino and visited him there from time to time) difficult to countenance or to write about. In the years before the 1914-1918 war he threw what time he had left after his semi professional pursuits into Esperanto, which he considered a force for good and for world peace. He created an Esperanto group in Bordighera, photo above. In 1914, when World War I broke out, Clarence was at the Esperantist Congress in Paris looking after a party of blind Esperantists whom he safely escorted back to their homes in Italy

He may not have been paying homage to an established religion but his heart was in the right place.

Excerpt from “A High Way to Heaven” by Christopher Chippindale.

Chapter on pages 21 and 22 “An English Chaplain and His Museum”

Further reading on this web site:

As part of research for a new biography of Clarence Bicknell, writer Valerie Browne Lester has been looking into the key characters in the Brotherhood of the Holy Spirit at Stoke-upon-Tern. Buy the book at www.clarencebicknell.com/shop or download her January 2015 research paper An Early Influence On Clarence Bicknell: The Rev. Rowland William Corbet (1839-1919) by clicking here.

Clarence Bicknell – All Saints Church Bordighera archives

by Graham Avery, original research in 2017 into the archives which are kept in London’s Metropolitan Archives, and the accompanying photos of the archives;

Clarence Bicknell – All Saints Church Bordighera archive photos

Clarence’s Bible “My mother died at 7.30 a.m., March 6th, 1850. When saying goodbye to my eldest brother Herman, she said, ‘I know that at the present day there are many temptations to infidelity. Do not be led away by them, whatever may be the arguments of those who support them. I wish to be interred in Norwood Cemetery. I wish my funeral to be as plain as possible. I hope that you will think of me when I am gone, even as I have thought of you. I rely firmly on the wisdom & goodness of the Almighty, and look forward to a cheerful immortality Without that hope these moments would indeed be dreary. God bless you.’ Transcribed by Valerie Browne Lester, May 2014 |