Clarence Bicknell (1842-1918) – Essentially Victorian

by Peter Bicknell

The mini-biography below was written by Peter Bicknell in 1988 and has been on this page of the website since 2013. In 2018 the authorised biography was published in book form, MARVELS: The Life of Clarence Bicknell, Botanist, Archaeologist, Artist by Valerie Lester. The book is available for sale on this web site (click on Shop), at bookshops and at Amazon. You can also consult or search the index of MARVELS; click on index.

Who was Clarence Bicknell? Why, more than a century and a half after his birth, are we as interested about him as always? Almost every year a new biography appears on a captivating personality, such as Jane Austen or Garibaldi, the “new” study largely repeating facts already stated by previous authors. Would it not be better to know other lives, not those geniuses, but lives that deserve to be told. Clarence Bicknell lived one of those lives. He lived his life by the image, so this web site and the biography in book form are illustrated throughout.

Clarence Bicknell was born in 1842, when Queen Victoria had only been on the throne for five years. When she died he was in his sixtieth year. So he was essentially a Victorian. In 1878, at the age of thirty six, he settled in Bordighera in Italy which was his home till he died forty years later. So for more than half his life he was a Bordigheran. He died in 1918, in the last few months of the war that was to end wars. It was a significant date, as it marked the end of an epoch.

Clarence Bicknell was born in 1842, when Queen Victoria had only been on the throne for five years. When she died he was in his sixtieth year. So he was essentially a Victorian. In 1878, at the age of thirty six, he settled in Bordighera in Italy which was his home till he died forty years later. So for more than half his life he was a Bordigheran. He died in 1918, in the last few months of the war that was to end wars. It was a significant date, as it marked the end of an epoch.

William Bicknell (1749-1825) Clarence’s grandfather, had, early in the 19th Century, sold a prosperous, but to him uncongenial, family cloth business, to run an Academy for young gentlemen in the suburbs of London. He was a staunch Unitarian. According to his grandson Sidney, Clarence’s brother, he was a voracious reader, a charming and witty conversationalist, a dedicated and conscientious worker, a lover of music, liberal in religion and greatly beloved – epithets which could equally well be used to describe Clarence. William established a tradition of happy family life, based on a civilised appreciation of the liberal arts. John Wesley and his composer brothers Charles and Samuel were friends of the Bicknell family. William himself found his happiest moments playing the spinet, the harpsichord and the organ. Elhanan Bicknell (1788-1861) was William’s fifth child.

Clarence was the youngest of Elhanan Bicknell’s thirteen children. His mother, Lucinda (Linda to the family) was the third of Elhanan’s four wives. She was the sister of the artist, Hablot Knight Browne, “Phiz”, the illustrator of Charles Dickens’s novels. At the time of Clarence’s birth, the family was established at Herne Hill, a rural suburb of London, four miles south of St., Paul’s, in a substantial villa with extensive grounds.

Elhanan made a fortune out of a highly successful business as a merchant of refined sperm oil, at that time a worldwide source of lighting, particularly for streets and lighthouses. The firm of Langton & Bicknells had financial interests in fleets of whalers engaged in the South Sea fishing industry. This was specifically the pursuit of the sperm whale which is the romantic background of Herman Melville’s Moby Dick and some of Turner’s most dramatic paintings. One of the principal sources of inspiration for these paintings was a series of exciting incidents graphically described and illustrated in Beale’s Observations on the Natural History of the Sperm Whale. Elhanan owned at least four copies of this book, one of which he probably lent to Turner. Elhanan also put at Turner’s disposal one the firm’s portraits of a whaler by the marine artist Huggins as a model for The Whaler – now in the Metropolitan Museum, New York.

It was in about 1840, a couple of years before Clarence’s birth, that his father began to buy the works of art which were to form one of the great Victorian collections. His purchases were limited to the works of living British artists. After a visit to Italy he said that he didn’t give a damn for the works of old masters. Among the well known artists represented were Turner, Roberts, Stanfield, Etty. Callcott, Landseer, De Wint and Muller. David Roberts was his closest friend (they were buried side by side in Norwood Cemetery), and Clarence’s half-brother, Henry, married Christine, David Roberts only daughter. Elhanan generally bought his pictures from the artist and not through dealers. They were often personally commissioned. The works of fourteen artists were described in the great sale of 1863 as “Painted for Mr. Bicknell”. This method of buying brought him into contact with the artists whose company he loved and whom he entertained at Herne Hill. Clarence’s cousin, Edgar Browne, found Herne Hill delightful, not only on account of the profusion and excellence of its art treasures but for the certainty of meeting, particularly on Sundays, a number of men occupying distinguished positions in the art world.

Turner was a frequent visitor, and the Turner paintings and watercolours formed the most important element in the collection. The Ruskins were neighbours, and the young John Ruskin was constantly in the house studying the works of Turner. Denning, the director of the nearby Dulwich Art Gallery, a family friend and a regular member of the Herne Hill set, painted a watercolour (below) of six of Elhanan and Lucinda’s children in 1841, the year before Clarence was born. Edgar Browne found the company of the cousins highly agreeable.

Some of Elhanan’s children at Herne Hill (Denning, 1841). Herman is the eldest of these six.

Some of Elhanan’s children at Herne Hill (Denning, 1841). Herman is the eldest of these six.

The most remarkable of the boys was Herman, the eldest of this six, twelve years older than Clarence. He became a distinguished oriental scholar and traveller. He was the first Englishman to make the pilgrimage to Mecca totally undisguised. He was a passionate mountaineer who made more than one ascent of Vesuvius during an eruption, and survived a serious accident on the Matterhorn, later to make one of the early ascents of that mountain.

Herne Hill was Clarence’s home for the first twenty years of his life. Here he enjoyed the amenities of life in a large and happy family, in a prosperous comfortable, nonconformist, middle class atmosphere, in which an appreciation of the arts was encouraged. In this, Herne Hill was like many good Victorian homes. But it was exceptional in being not only a gallery of contemporary art, but also a kind of club for the leading artists. Count d’Orsay, working from a sketch of Landseer’s, published a lithograph of Turner in Mr Bicknell’s Drawing Room. It was not every Victorian boy who grew up in a home where there were more than thirty Turners to be seen, where he might find Turner himself having a cup of tea in the drawing room, or Ruskin discussing pictures such as Turner’s great Palestrina or his Fort Ruysdael.

Herne Hill came abruptly to an end in 1861 when Elhanan Bicknell died. Clarence’s mother had died in l850, and his father had immediately married his fourth wife. Clarence’s childhood was over. In 1862 he went up to Trinity College, Cambridge, to read mathematics. At the university he was much influenced by an enthusiastic group of young churchmen; and soon after he had graduated in 1865, he took orders in the Church of England, forsaking mathematics and the Unitarianism of his father and grandfather. For some years he acted as curate at Walworth, a tough parish in the slums of south London which supported the Order of St. Augustine, a passionate, ritualistic community, mysteriously linked with Rome. Here he lived a simple life, devoting himself and much of his income to the poorest people- notably during a devastating outbreak of smallpox. This pattern of simplicity, generosity and service was to be with him for life. He left Walworth and joined some of his Cambridge friends in The Brotherhood of the Holy Spirit in the village of Stoke-by-Tern in Shropshire, where he lived in a high church community devoted to the mission of preaching. After thirteen years he began to have serious religious doubts, and decided to avail himself of his inherited private means to see the world.

Among the many places which he was able to visit in the next few years were Ceylon, Morocco and Majorca. Finally he came to Bordighera, on the Italian Riviera, in 1878, invited by the Fanshawe family to act as chaplain to the English church.

But his religious doubts were growing. He found the church too ritualistic, too dogmatic and too chauvinistic. Within a year he had resigned. He gave up any active participation in church matters, asked not to he referred to as ‘The Rev.’, and ceased to wear a dog collar. He was later to say in a letter to a friend, “I fear I have become rather narrow about all church things, having become convinced that the churches do more harm than good & hinder human progress, & look upon the pope, the clergy & the doctrines as a fraud, though not an intentional one.”

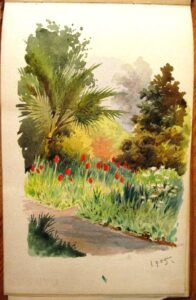

Watercolour of a Bordighera garden by Clarence

Watercolour of a Bordighera garden by Clarence

Though disenchanted with the church, Clarence had become enchanted by Bordighera, soon buying the Villa Rosa from Mrs. Fanshawe Walker and making it his home for the rest of his life. At that time Bordighera was almost an English colony. Indeed, towards the end of the century the English outnumbered the native Italians. It preceded the French Riviera – Menton, Monaco, Cannes etc. – as a popular winter resort. Foreign visitors, many of whom became residents, flocked there for the winter sun in a climate which was considered particularly beneficial for sufferers from the still incurable disease of tuberculosis.

Claude Barry (not Berry), Clarence’s sister’s son, a talented artist, came to Bordighera suffering from “galloping consumption”, and lived to inherit his father’s baronetcy and pass it on to his son Sir Rupert Barry. By a happy coincidence Mari Henderson (now my wife Mari Bicknell) as a child, long before she knew any Bicknells, was taught drawing by Barry when her family spent some months in the Berry’s (not Barry’s) Villa Monte Verde.

Clarence immediately became involved in the activities of the English colony – activities leading to the building of his museum, the foundation of the International Library, the organising of lectures and concerts and so on. But he was also deeply involved in giving generous active and financial help to the poorer of the resident Italians, notably after the severe earthquake in 1887.

Some idea of Clarence’s character is given in the appreciations written by Edward and Margaret Berry after his death. But it must be kept in mind that the Berrys always saw Clarence through rose-coloured spectacles.

“He roamed over the hills seeking rare flowers, but noticing everything – small insects, birds, stones, light and cloud effects, and talking in his gay and eager way to everyone he met… His lively conversation, full of sparkling wit and humour and the wonderful letters that he used to write, illustrated with pen and ink sketches, are precious memories to those who were privileged to call themselves his friends… He was greatly loved by the Italian population… who recognised in him an unfailing helper and adviser in all their needs material and moral. The familiar figure, in loose flannels, with open collar … with an immense grey felt hat on his head, was always welcome… Intensely affectionate and emotional, he was inclined to violent prejudices, from which he could not always easily free himself and the haste with which he threw himself into new intimacies was a standing joke amongst his old friends.”

Clarence painted the shutters of the Casa Fontanalba with flowers and inscriptions in Esperanto. This one says “Pro multo da arboi, li arbaron ne vidas”, that is, “He does not see the wood for the trees”.Clarence’s principal passion was the study of botany and a love of flowers. The richness of the flora of Bordighera and its neighbourhood was for him one of its main attractions. In them he found a wonderful source of inspiration. He immediately set about collecting the plants and recording them in explicit and attractive watercolour drawings.

By 1884 he had made over a thousand of these drawings, 104 of which he selected as illustrations for his Flowering Plants and Ferns of the Riviera and Neighbouring Mountains, published in 1885. For these lithographic plates the original drawings were all redrawn. They show his highly developed sense of design combined with skill in producing accurate and informative botanical images. Eventually 3,349 of his botanical drawings were deposited in the Botanical Institute of Genoa University. He also created a remarkable herbarium of dried specimens which is also at Genoa.

In the last decade of the nineteenth century Clarence’s life was significantly enriched by the advent of the Berrys to Bordighera. They became his closest friends, sympathetically involving themselves in his activities and, after his death, becoming the custodians of his enterprises. It was in 1881 that the son of Clarence’s sister Ada, Edward Elhanan Berry, came to Bordighera as manager of a bank, as Thomas Cooke’s agent, and later as British vice-consul. Five years later Margaret Serocold came to her family’s villa. And in 1897, Edward and Margaret were married. In 1904 they laid the foundation stone of the Villa Monte Verde. A photograph of the ceremony shows Clarence uncharacteristically wearing a bowler hat.

The relationship between Margaret and Clarence is beautifully illustrated by the story of the vellum albums. Shortly after her marriage Margaret saw in Lorenzini’s shop in Siena some exquisite books of superior drawing paper elaborately bound in white vellum. She bought one and gave it to Clarence. He was delighted. A few months later he gave it back to her, now filled with flower designs. Next time Margaret was in Siena, she bought one and repeated the gift; and again Clarence returned it to her transformed. This became a ritual. At least once a year until the outbreak of war in 1914 an album was exchanged and dedicated to Margaret Berry.

The vellum-bound Casa Fontanalba Visitors’ Book by Clarence Bicknell

The vellum-bound Casa Fontanalba Visitors’ Book by Clarence Bicknell

Seven of these are now in the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, as part of their outstanding collection of flower paintings. Each album has a theme – for instance, one is a book of marguerites for Margaret; one is a Book of Berries for the Berrys; another is a book of flowers from the Val Fontanalba; another is a book of poems decorated with appropriate flowers. The album dated 1911 is a coronation procession of the flowers of Fontanalba to celebrate the coronation of King George V. The last dated 1914 is an elaborate fantasy, The Triumph of the Dandelion in which the flowers compete for the crown of the Beauty Queen of Fontanalba. Page by page each flower presents her claim in enchanting drawings, supported by descriptions of her charms (sometimes medicinal) in prose and in verse (often facetious). One of his finest albums is the Children’s Picture Book of Wild Plants of 1908 which is a complete botanical catalogue of 404 wild plants, each with an immaculate water-colour drawing, that grew wild in the garden of the Casa Fontanalba. The book ends with the couplet,

“Now if you say, Oh what a show of plants.

“Now if you say, Oh what a show of plants.

I beg your pardon.

This book is finished; not so the treasures

of my garden.”

Clarence continually expressed his preference for wild plants rather than garden varieties. His delight in playful fantasy has much in common with the nonsense of Edward Lear and Lewis Carroll. He loved puzzles, riddles, jokes, puns and parlour games. For Margaret Berry he made a botanical version of the popular Victorian game of happy Families.

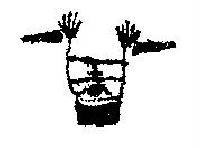

His childish sense of fun often invaded the area of scientific order. His drawing of a cat on a log is the title on the cover of his official catalogue of the 10,000 rock engravings which he identified in the Vallée des Merveilles. Sometimes scientific order invaded the area of fun – when, for instance, as an inveterate collector, he mounted and catalogued his collection of misaddressed envelopes: “Al Illustrisimo Signor Bick – Bihl – Bigi – Bequenelly – Boiocinello – Bicknelli Florence – Binil Milord Clarence – Madame Brickerelle – Egregio Signor Bicnet Franco” are some of the names that rewarded him for his enormous correspondence. He must often have signed his name illegibly in the hope of adding to the collection.

As an artist he was versatile. He would try any medium. He had a particularly strong sense of design; he did poker work on bellows and boxes; he made furniture; he made rugs of many coloured wools; he decorated ceramics, such as the splendid umbrella stands for this museum. Late in life he was studying a new method of sketching in sanguine and pastel, under the instruction of two Belgian artists, father and son Van Biesroech.

Christopher Chippindale has pointed out that the humane rational spirit which Clarence Bicknell showed, particularly in old age, was characteristic of liberal progressive thinking of the period. He was a pacifist who devoted himself to works of war charity in times of war; an enthusiastic supporter of women’s suffrage who deplored the excesses of the suffragettes; a vegetarian who never embarrassed others with his prejudices; a man of means who lived in simplicity and devoted his means to others; a master who treated his servants as friends, and embarrassed hosts and hotels by expecting his companion Luigi Pollini to be treated and accepted as a guest and not a servant.

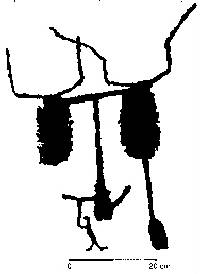

It was not till 1905 that Clarence embarked on the enterprise of building a house for the summer at Casterino. He had first visited the Vallée des Merveilles on the west side of Mont Bego in 1881. With further visits in 1897, 1898, 1901 and 1902, and the discovery of more rock engravings in the upper Fontanalba valley, on the Casterino side of Monte Bego, the study and recording of the engravings (images of Le Sorcier and Oxen below) had become almost as absorbing of his energies as the flora; and Casterino was an ideal base for the field work of both activities.

The Casa Fontanalba, always referred to by Clarence and his English friends as ‘the cottage’, was designed by the British architect Robert Macdonald, in the very British sub-Georgian tradition of the Empire. It is neither Italian nor French; nor is it a ‘cottage’ nor a ‘chalet’.

The Casa Fontanalba, always referred to by Clarence and his English friends as ‘the cottage’, was designed by the British architect Robert Macdonald, in the very British sub-Georgian tradition of the Empire. It is neither Italian nor French; nor is it a ‘cottage’ nor a ‘chalet’.

The Berrys, now his close companions and friends, were deeply involved. Three of the four brothers, Edward Elhanan of Bordighera, Sir James a distinguished surgeon, and Arthur of King’s College Cambridge, Professor of Mathematics, with their wives, gave active help clearing the surroundings of the site and preparing the garden.

Luigi Pollini, son of his faithful servant Giacomo, and now Clarence’s constant companion and assistant in his work, referred to by Clarence as his ‘factotum’, built garden sheds, garden paths, bridges, planted trees and prepared and tended a fruitful kitchen garden. The house was furnished with extreme simplicity “with wooden bedsteads, American folding chairs, without wardrobes, carpets or hangings”. Clarence himself carried out an elaborate scheme of decoration based on conventional interpretations of the flora and the engravings… with much use of patterns horns over doors and windows, to prevent the entrance of evil spirits, goblins, witches etc., all combined with sentences and proverbs in Esperanto.

The Casa Fontanalba was restored in the mid-1980s to its original form by the removal of some minor additions. Nothing remains of the garden which has returned to nature. Surrounding trees, mostly larches, have grown and multiplied so that the site looks very unlike it did when the house was originally built.

Clarence had become enthusiastically involved with Esperanto, the international language which had been thought up in 1887 by Dr. Zanenhof, an oculist in Warsaw. In it Clarence saw a medium which could unite mankind in peace and loving friendship. in a way which the Christian faith, with its acceptance of the tower of Babel, had failed to do. With characteristic energy he devoted himself to the cause, organising an Esperanto Centre in Bordighera, annually attending conferences from Cracow to Barcelona (generally accompanied by Luigi), translating into Esperanto poems such as Macauley’s Horatius, and winning prizes for his own Esperanto poems. In 1914 when war broke out he was in Paris looking after a party of blind Esperantists whom he safely escorted back to their homes in Italy. In his seventies he would rise at 5.30 in the morning to apply himself to the task of typing Esperanto poems in Braille.

The names of everyone who spent a night in the Casa were recorded decoratively on the walls of one of the rooms. And one of the vellum albums was filled with entries cataloguing these people with biographical notes in Esperanto.

The entry for Emile Cartailac, Professor of Pre-History at Toulouse, who came to see the Merveilles, is decorated with a device which was frequently found amongst the engravings. This seems to show two pairs of horns, some straight lines and a human figure. It had been a great puzzle to Clarence, until one day he noticed and photographed a primitive plough drawn by two oxen still in use near Casterino, and realised that the horn shapes represented the oxen, straight lines the plough and the figure the ploughman. There had been no change since the bronze age.

It was at Casterino that Clarence made most of studies – rubbings, drawings and photographs – of the rock engravings. And it was at Casterino that he spent the happiest days of his old age. Luigi Pollini, who had become his gifted and efficient assistant, was his constant support. Clarence remained amazingly energetic. In 1914, when he was 72, he was planning a visit to Japan, travelling by the trans-Siberian railway; but he called it off, as he thought Luigi was not strong enough to accompany him. Those who knew him in his last years say that he was indefatigable. He would spend the day with his friends, energetically showing them the Vallée des Merveilles and the flowers, entertaining them enthusiastically. Then when they had retired exhausted he would get down to serious drawing, letter writing, or some other task. Next morning he would be up long before them, collecting specimens or drawing again.

On a sunny day in July 1918 Luigi carried Clarence Bicknell out onto the terrace of his ‘cottage’ where he died peacefully, in the surroundings which he loved, encircled by the mountains which he knew as ‘The Gate of Heaven’.

Clarence Bicknell born in Herne Hill, 27 October 1842

died in Val Casterino di Tenda, 17 July 1918

buried in Tende (now part of France)

This article was originally a talk given by Clarence Bicknell’s great-nephew, Peter Bicknell, in the Museo Bicknell in Bordighera, Italy, on 23 September 1988, as part of the celebrations of the centenary of the opening of the Museum. It accompanied 41 magic-lantern slides which are still in the family collection. You can download the original version of Peter Bicknell’s talk here. Reproduced by kind permission of Mari Bicknell.