What is it about the human brain which makes collecting so compulsive?

Many people find delight in hobby collecting; certain types of antiques, Toby jugs, Fabergé eggs, medicine jars, French pochoir fashion prints of the 1920s or garden gnomes. Children (and grown-up children) like to collect toys, especially when they make a set; an HO-scale model railway, Lego space ships, Formula 1 racing cars in 1/43rd scale, Barbie dolls or Teddy bears by Steiff. Others place high value on cigarette cards, postage stamp, Pokemon cards, Marvel comic books, quartz pieces, stickpins and coins… especially if the collection has a theme or specialisation.

As the age of reason progressed through the industrial revolution, scientists made collections for a higher reason – to understand. The process of “collecting” includes prospecting, travelling, searching, packing, transporting, analysing and displaying. The process is an important way for collectors to study and learn about what they’re collecting.

Since late in the 15th century, a number of authors, led by Carolus Linnaeus, had become concerned with what they called methodus (method), an arrangement of minerals, plants, and animals according to the principles of logical division. Collecting is the basis of a museum; the UK’s great public collections grew from the obsessions of such cultural omnivores as the much-travelled physician Hans Sloane, whose collection both formed the 18th-century kernel of the British Museum and seeded the Natural History Museum1. Like Sloane but 100 years earlier, John Tradescant started as a naturalist collecting specimens. Tradescant entreated merchant voyagers to bring back from “Turkye, Gine, Binne, Senego, Constantinoble, the Newfound Land, and the New Plantation towards the Amasonians, Anything that is strang” (sic, without the e). These went to fill what became known as Tradescant’s Ark. Together with the trophies of nature came artefacts like “shoes to walk on snow without sinking”, which marked the origin of that oddly Eurocentric discipline, ethnography – as if we were not ourselves “strang“. Tradescant’s son continued the enterprise, leaving the treasure house to his widow Hester, who fell victim to the wiles of Elias Ashmole, a zealous visitor and adviser who turned out to have a terminal case of the collecting disease: he collected collections. The duped widow, failing to regain her title to the hoard, committed suicide. The museum’s name – Ashmolean – celebrates Ashmole’s coup.

In modern times, “collecting” is part of the intellectual overlay of learning. Benjamin Bloom (1956) developed a classification of levels of intellectual behavior in learning. This taxonomy contained three overlapping domains: the cognitive, psychomotor, and affective. Within the cognitive domain, he identified six levels: knowledge, comprehension, application, analysis, synthesis, and evaluation. Collecting is for Bloom the starting point of knowledge.

In any case, by the time of Grand Tour in the 18th and 19th centuries, when young English gentry visited France, Italy and other centres of art and culture, it would have been considered natural to “collect”2. Certainly, for Clarence Bicknell, it was natural to “collect”. In every dimension of his interests we find him grouping many objects or ideas together for the purpose of understanding them.

Clarence is well known for two “collections” which marked his life and created the legacy he left us.

First were his botanical drawings of which he had completed over a thousand by 1884, 6 years after settling in Bordighera. These were the subject of his highly-respected illustrated book Flowering Plants and Ferns of the Riviera and Neighbouring Mountains published in 1885. His excursion sketchbooks of the 1890s continue to list flower species so his Flora of Bordighera and San Remo, an un-illustrated list published in 1896 is focussed in geographical scope.

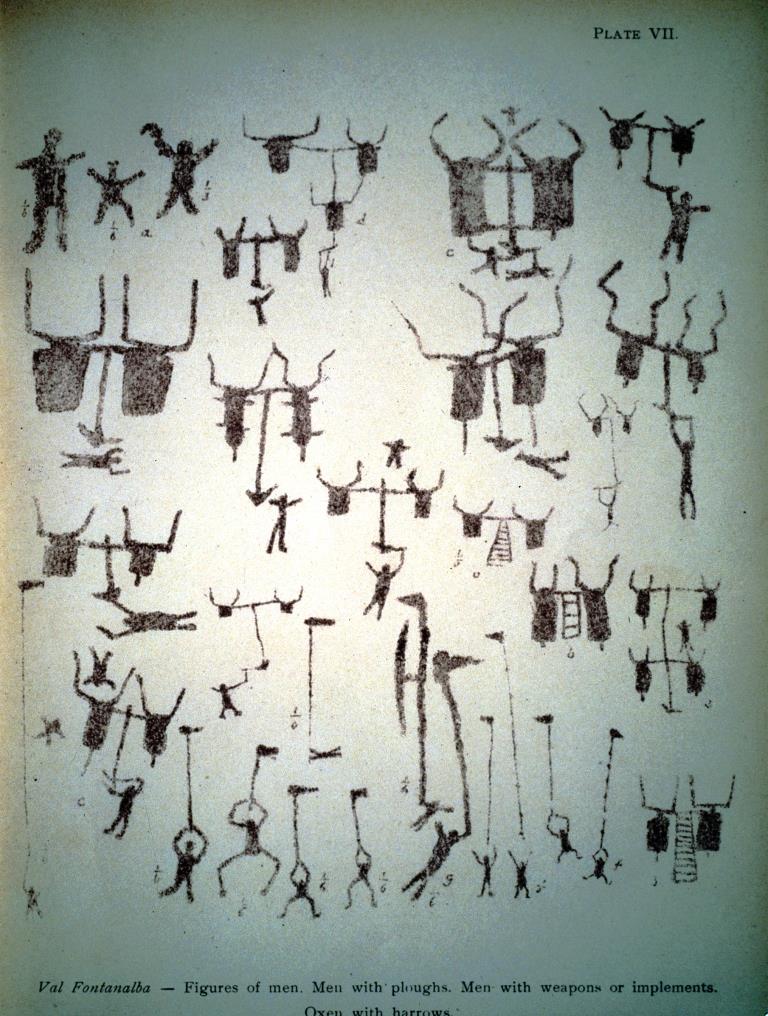

Secondly, the rock engravings. Clarence first visited Vallée des Merveilles and Val Fontanalba in 1897; this is the date at which Clarence’s interest was first captivated by the mysterious marks on the rock. He rented a house at Val Casterino for the first time and started rubbings of the engravings, i.e. he was just recording them. This same year he made a preliminary report to the Society of Antiquarians of London (published in its proceedings) and read a paper to the Societa Ligusticà in Genoa. By 1902 his “collection” of rubbings, drawings and photographs of the rock engravings was substantive enough for him to publish A Guide to the Prehistoric Rock Engravings in the Italian Maritime Alps. In the following fifteen years the number of rock engravings he had recorded in the Vallée des Merveilles and the Val Fontanalba surpassed 10,000 in number; the 1913 edition of the same book remains the preferred reference book and it was reprinted in three languages by the Istituto Internazionale di Studi Liguri in 1971. The page from his book, left, is typical of his collecting various images together to compare and categorise them.

Further “collections” throughout his life showed that Clarence had this instinct for recording items in large n umbers to be able to compare and comprehend. Throughout his life Clarence drew sketches in pencil, ink or watercolour. Other subjects became a brief obsession for him as he analysed them in the variations…

On his trip up the Nile over New Year 1889-90 Clarence made numerous “flying sketches” of Nile sail boats as he calls them in the diary which they illustrate. We count 44 exquisite and detailed water colours of these boats, with apparent fascination for the angle of the boat in the water and of the sail to the boat. One of several pages is shown top right. Download our article with excerpts at Clarence Bicknell – Diary: Nile Cruise (1889-1890)

On his first trips up to Casterino his eye was taken with the sheep in the upland pastures. For days on end his sketch book is full of sheep, single, together, from all angles.

His landscapes show themes as any artist’s would; but in Clarence’s case he would stay for several days with one theme at a time such as architectural details in Swiss and Italian cathedrals (1882-3), the rocky west coast of Ireland (earlier in 1889), the mountains viewed from different points in Casterino and the area (1898-1900) or a village in the Cuneo valley; each subject shown in a multitude of sketches.

In his early days in Bordighera, Clarence collected hundreds of different species of butterflies. Mounted and glassed in wooden drawers, the butterfly collection can be viewed at the Museo Bicknell in Bordighera.

Clarence’s collection of stuffed birds is less well known but just as impressive. He collected fossils and minerals which he showed to visitors to the Casa Fontanalba3

In the Casa Fontanalba, Clarence’s instinct for repetitive themes in decoration came to a delightful fulfilment. He was aware that he was creating a building, decorations and books which would be part of his legacy “for those that come afterwards” and here was a place where he had solo control. The wall decorations use the forms of the rock engravings and the flora of the area in the friezes and door surrounds. The window shutters use both the flora and his “collection” of proverbs in the Esperanto language. The Casa Fontanalba Visitors’ Book, signed by everyone who came to the house (or stayed a night – we are uncertain), is illustrated, page after page, with simple but beautiful water colours of flowers of the region. The borders of each page are illuminated with repetitive use of a feature of the flower, in a style reminiscent of the Arts and Crafts movement of William Morris and others. The book in which he wrote snippets about the more important people (and dogs) in his life (which I refer to as the Book of Guests in Esperanto) and the vellum album of four-to-a-page flowers from the Casa Fontanalba garden are treated similarly: formatted, in orderly form, and decorated …as collections.

Even when expressing his sense of humour, Clarence made a collection out of every gesture. Clarence wrote many letters, so he received many. The incorrect spellings of his names were so numerous that Clarence kept, for his amusement, every single envelope in a collection still in the family’s possession. For Margaret Berry, Bicknell made a botanical version of the Victorian game Happy Families. There are four flowers each from 16 flower families, plus six extra jokers, each painted in watercolour. Each year, in a family tradition, he painted for Margaret Berry a watercolour album on a chosen theme: a book of marguerites for Margaret, a book of Berries for the Berrys, and The Triumph of the Dandelion in which flowers compete for the crown as Beauty Queen of Fontanalba.4

That makes at least nine different aspects of Clarence’s creative output which can be considered collections. Clarence acknowledged indirectly his instinct as a collector. Of the rock engravings, in the early stages of research, he wrote “We are only the collectors of facts, and must leave to others the task if studying them more profoundly”. This might be false modesty because he was inexorably led up the path of curiosity and comprehension. But his interpretation was always based on his own findings in the field. He became very good at identifying the forms of the engravings: famers working, tolls and implements, oxen ploughing, cattle enclosures and sacred images. His interpretations (and the way in which similar icons are grouped on the page… collections) pervade his writing including A Guide to the Prehistoric Rock Engravings in the Italian Maritime Alps.

Christopher Chippindale says; “What is a field naturalist to do? First, to search and find. Then, to record and describe. Then , to classify. All these things Bicknell did…” The instinct to collect was a fundamental part of Clarence’s work and play, and therefore of his legacy. Clarence himself is rather collectable which is why we enjoy researching his life and work. In this case, there is only one of him.

Marcus Bicknell, March 2013

1 From the review by Tom Phillips of To Have and to Hold by Phillip Blom 2002

2 At its extreme, in the case of archaeology, Thomas Bruce, the 7th Earl of Elgin obtained a controversial permit from the Ottoman authorities to remove pieces from the Parthenon while serving as the British ambassador to the Ottoman Empire from 1799 to 1803. The Elgin marbles are still in London’s British Museum. Clarence Bicknell may have been less extreme than Elgin, but his critics might remind us of the one or two loose rock engravings which he removed from the Vallée des Merveilles.

3 “Mr. Bicknell’s garden is a variegated blaze of colour, since it is principally dedicated to flowering plants . Adjoining it is a substantial stone building, in which the founder, who is the author of an excellent Flora of Bordighem and San Remo, and other works, has brought together a very complete local herbarium and collection of fossils, minerals, and prehistoric objects.” from “Wanderings on the Italian Riviera : the record of a leisurely tour in Liguria” by Frederic Lees 1913.

4 Description from Christopher Chippindale’s A High Way to Heaven 1998

Helen Blanc-Francard writes, in May 2017…

Living at Casterino was much more that just a convenient base for collecting herbaria samples and studying rock engravings, it represented something of a utopic escape ‘ a free and healthy life’. Bicknell could leave behind the chattering ‘tea room’ gossip and, in the fine Alpine air, immerse himself in a single-mindedly pursuit of his passions. – He is so anxious to please everyone and his empathy and naturally generous spirit is, once again, evident: he is keen to share his discoveries and shows his egalitarian concern and respect for Luigi.Like many collectors, he is definitely rather obsessive about seeking out botanical specimens – known and unknown. – Pursuing this thread (and not being a collector myself), I found a most interesting Wiki page that discusses the psychology of collecting and the factors that motivate people to devote great amounts of time, money and energy to creating and maintaining collections. It provides food for thought with respect to Clarence:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Psychology_of_collecting

The natural history craze of the Victorian era opened opportunities for the development of many entirely new commercial ventures. Not only for the sale of literature but also for all the equipment and paraphernalia (including the manufacture of microscopes, lenses, cabinets and supports) associated with sample collecting, studying and identifying, but specimens too could be bought and sold. This is what Wiki says: “Natural history specimen dealers had an important role in the development of science in the 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries. They supplied the rapidly growing, both in size and number, museums and educational establishments and private collectors whose collections, either in entirety or parts finally entered museums. Most sold not just zoological, botanical and geological specimens but also equipment and books. Many also sold archaeological items. They purchased specimens from professional and amateur collectors, sometimes collected themselves as well as acting as agents for the sale of collections. Many were based in Amsterdam, Hamburg and London and in other major cities. Some were specialists and some were taxonomic authorities who wrote scientific works and manuals, some functioned as trading museums or institutes”.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_natural_history_dealers

Fast forward to Clarence’s (very disjointed) 1916 letter to Ellen Willmott where there is an oblique reference to his Great War effort that, if the following website is to be believed, was very significant.

Onwards now to the flora and fungi: Ellen Willmott was a recognized authority on the genus Narcissus. The Narcissus Tazetta L. is described by Clarence. It flowers from February to April depending on the site and altitude. So we know that he ate mushrooms in 1916 “last summer’s gatherings …” “Marasmius oreades, the Scotch bonnet, is also known as the fairy ring mushroom. The name tends to cause some confusion, as many other mushrooms grow in fairy rings (such as the edible Agaricus campestris, the poisonous Chlorophyllum molybdites and many others). This mushroom can be mistaken for the toxic Clitocybe rivuloa. Many mushroom connoisseurs are fond of M. oreades and its sweet taste lends it to being baked goods such as cakes. It is also used in foods such as soups, stews, etc. Traditionally, the stems (which tend to be fibrous and unappetizing) are cut off and the caps are threaded and dried in strings”.