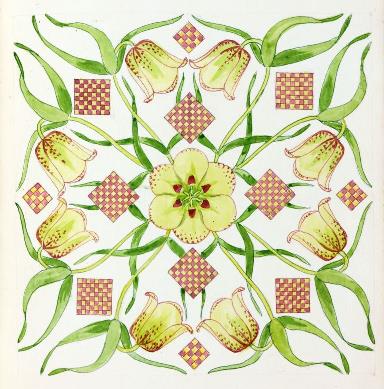

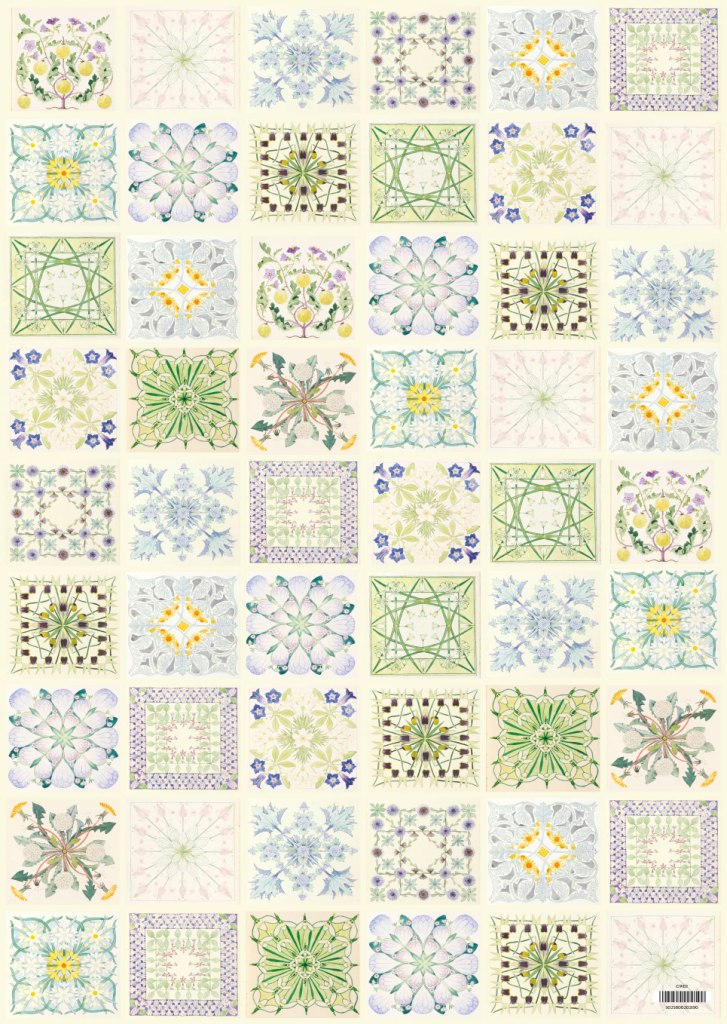

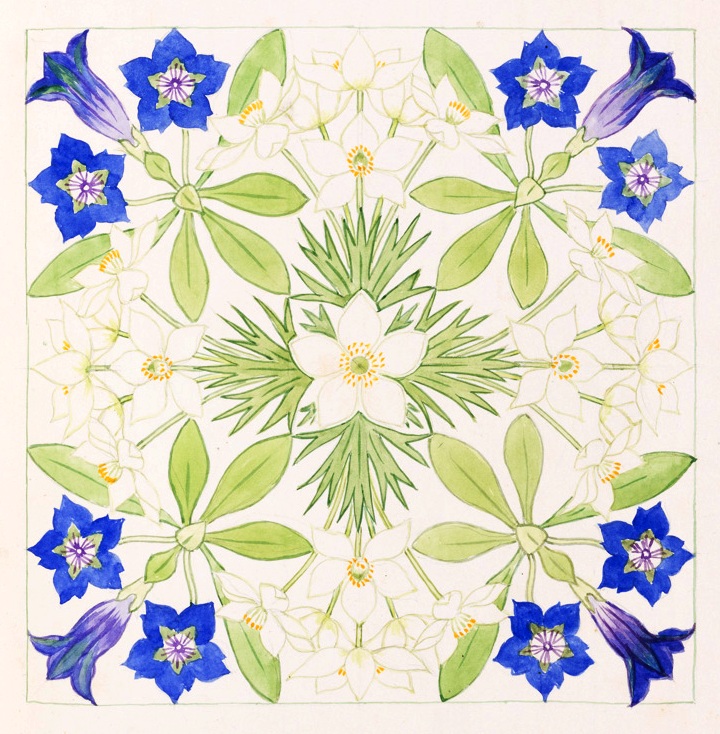

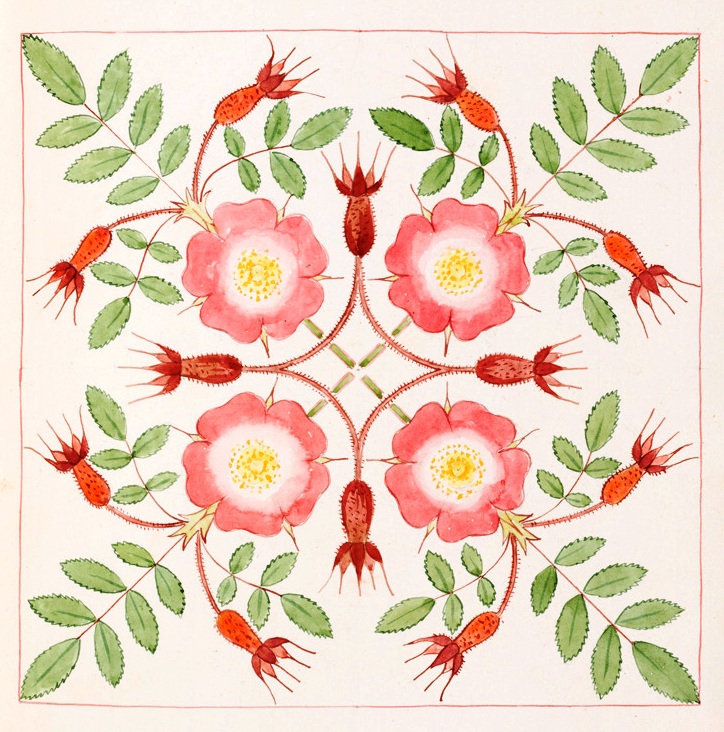

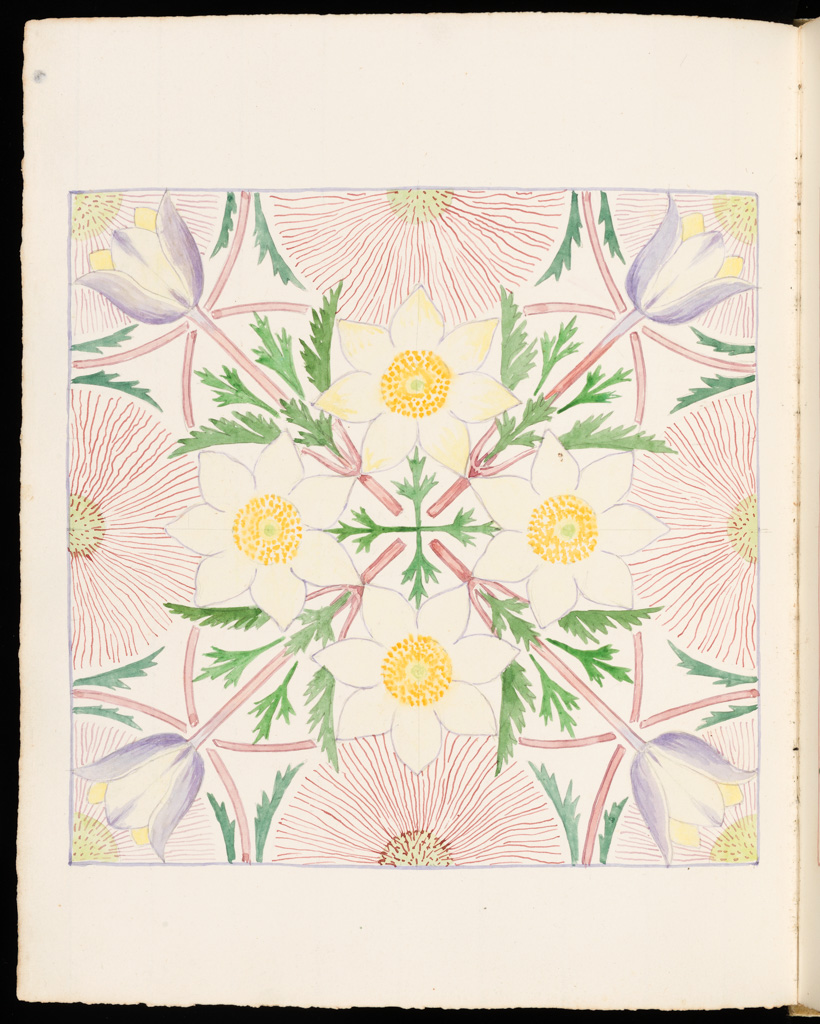

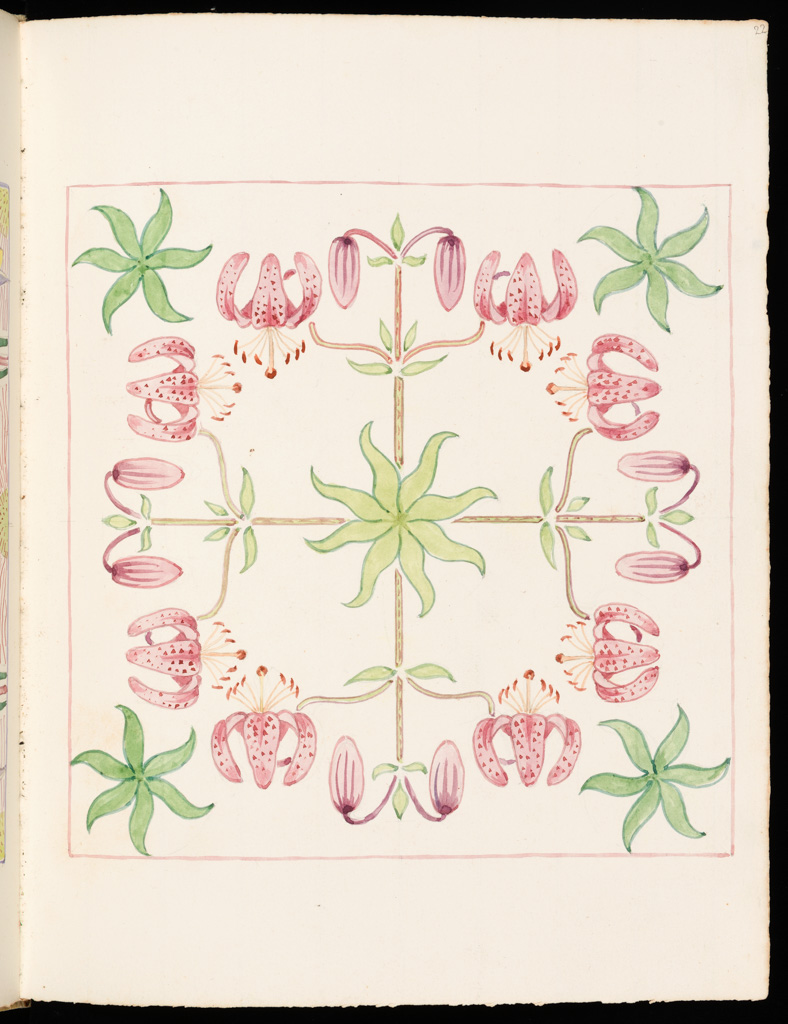

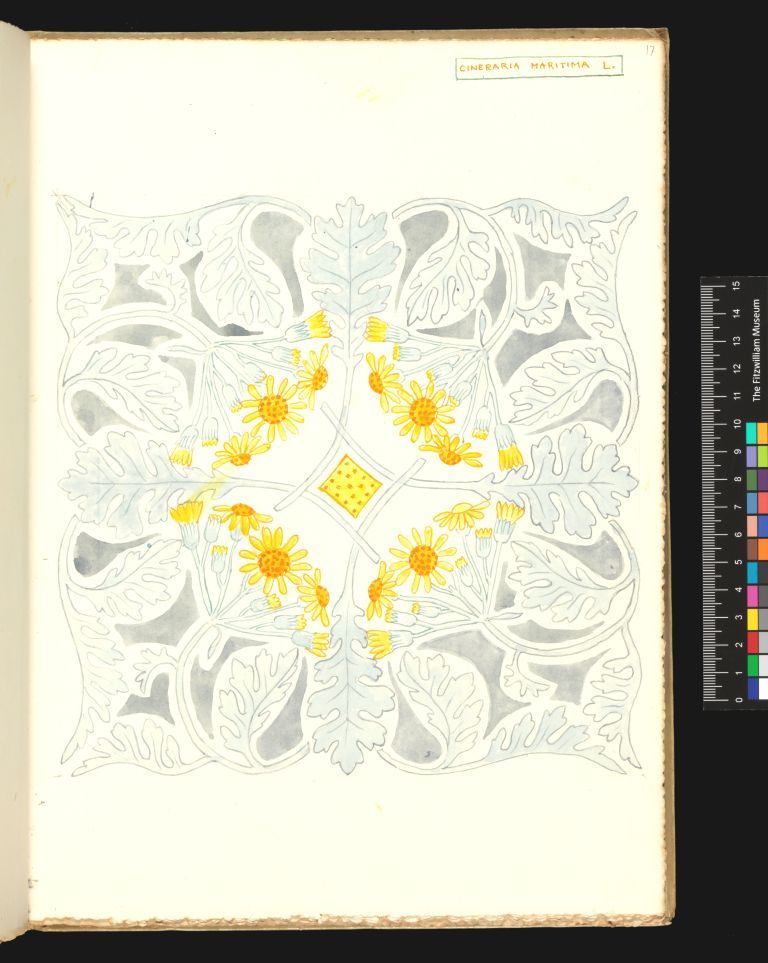

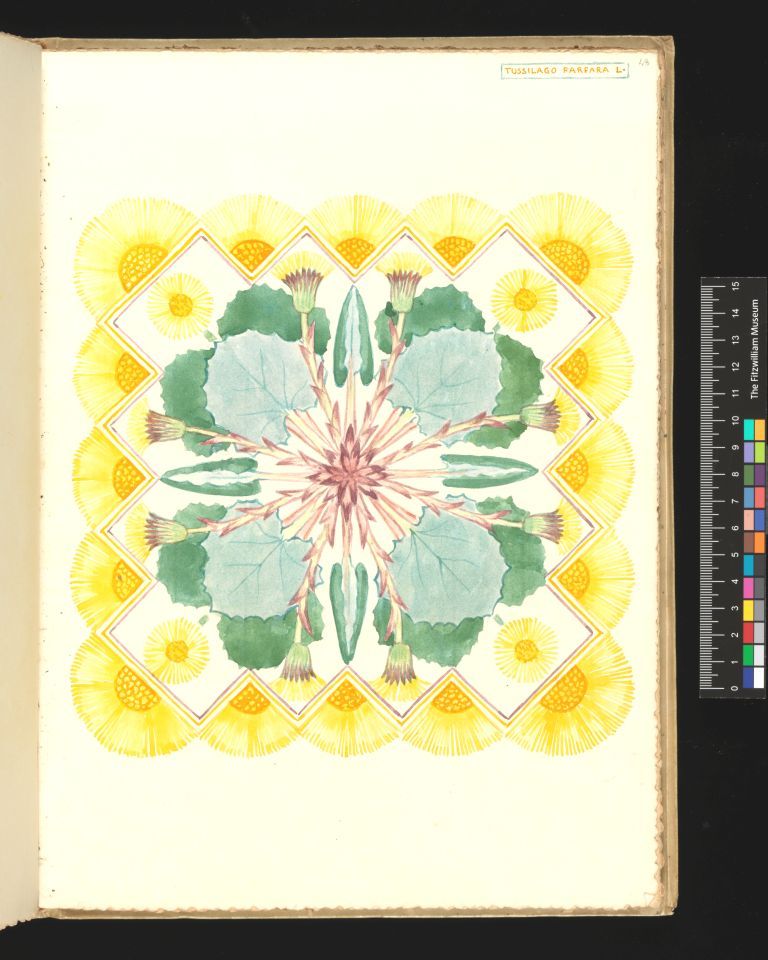

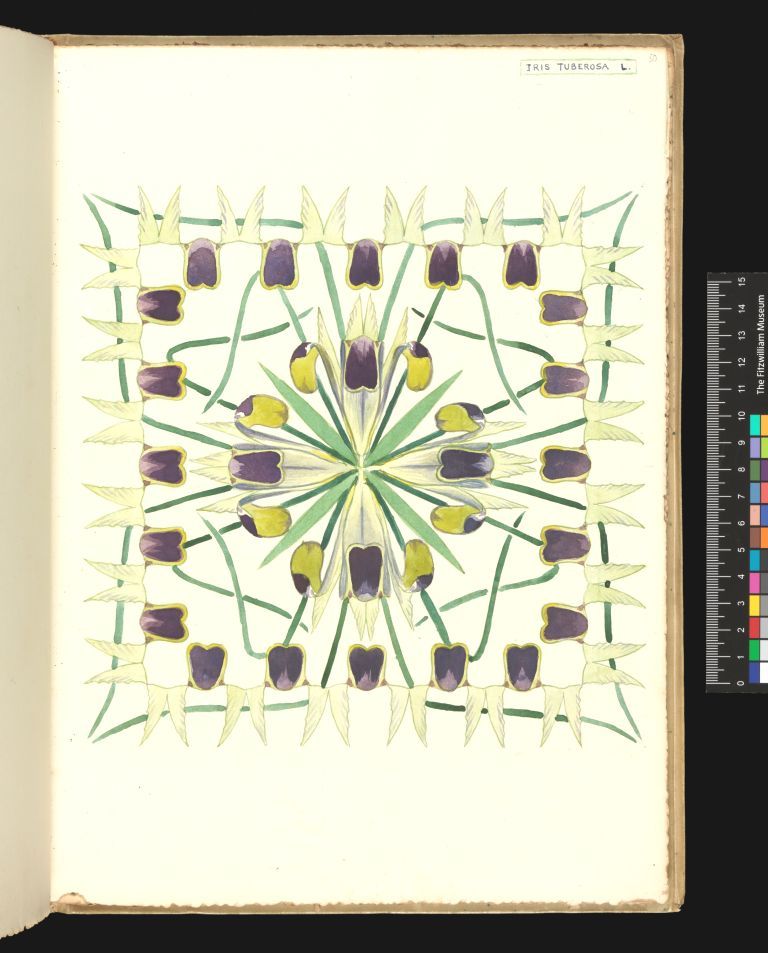

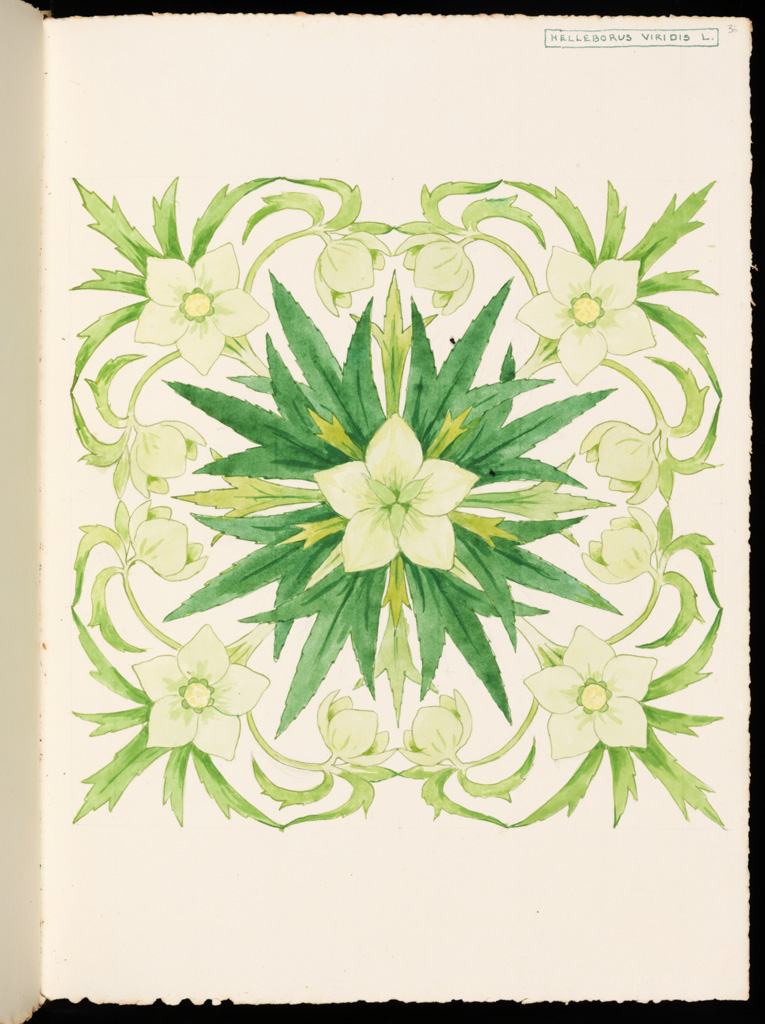

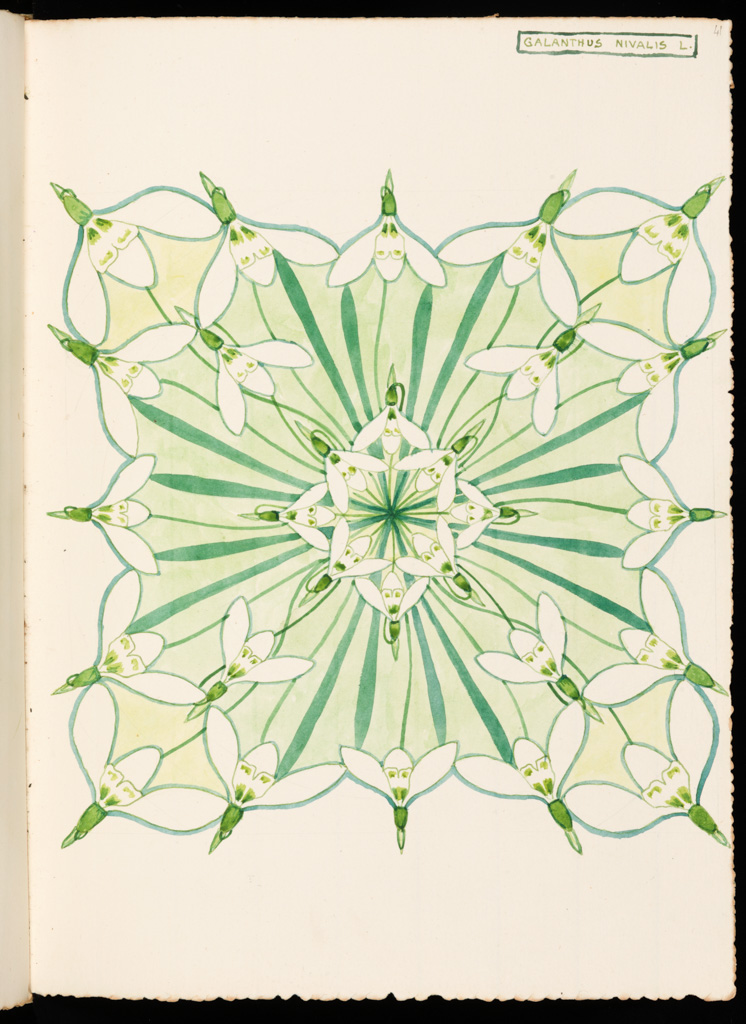

Some of the most startling and innovative Clarence Bicknell’s creations are in the seven albums in the Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge. Peter Bicknell, Marcus’s uncle, donated the vellum-bound albums to the museum in 1980, comprise 405 pages of watercolour paintings, many of them photographed and available for us to enjoy. The books encapsulate the last stage of Clarence’s artistic journey from rigorous botanical recording of the late 1870s through the floral decorations of the Casa Fontanalba Visitors’ Book to these idiosyncratic arts and crafts creations full of wit and whimsy. The Fitzwilliam has generously allowed us to reproduce (but not in the original high definition) these extraordinary images; they are so popular that reproductions of them as greetings cards and other merchandising are best-sellers in the museum shop and around Britain. Read more below the picture gallery…

Experts rate Clarence Bicknell’s symmetrical floral patterns alongside the greats of the Arts and Crafts movement like William De Morgan and Walter Crane. “Symmetry is synonymous with beauty in art” https://www.demorgan.org.uk/exhibitions/sublime-symmetry/. They certainly catch the eye in the gallery of images from the albums

The seven albums are

1. Sketchbook. A Book of Berries. 1908. Clarence loved word plays. The “Berries” were not just the small, pulpy, and often edible fruit in the design but also his nephew Edward Berry and his wife Margaret who also lived in Bordighera and were a vital part of his team. It was she who bought a blank album every year for Clarence. He filled each with floral designs and often returned it to her as a gift. This album contains mostly symmetrical floral creations.

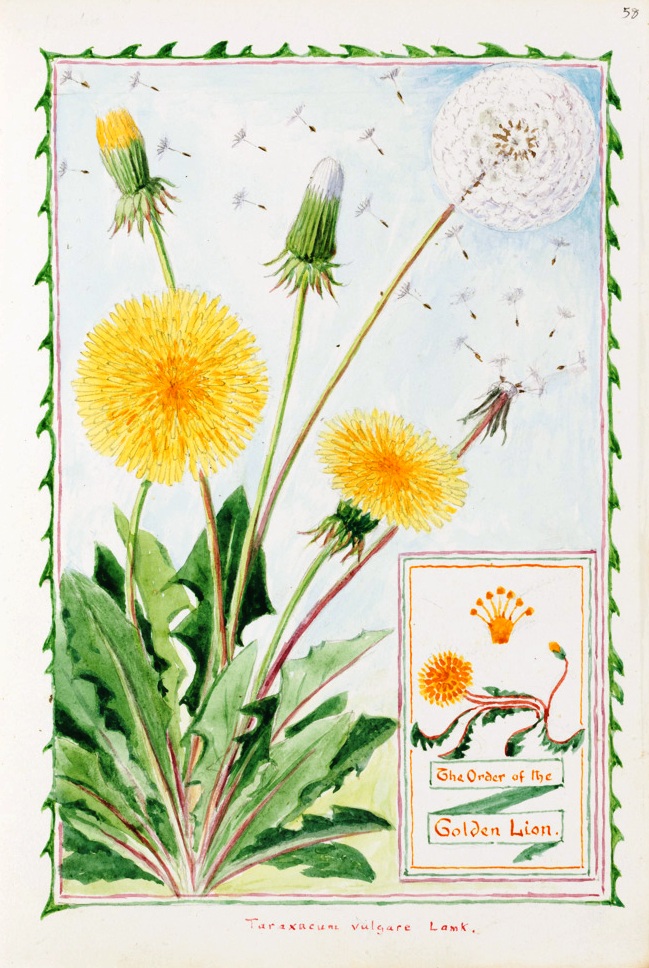

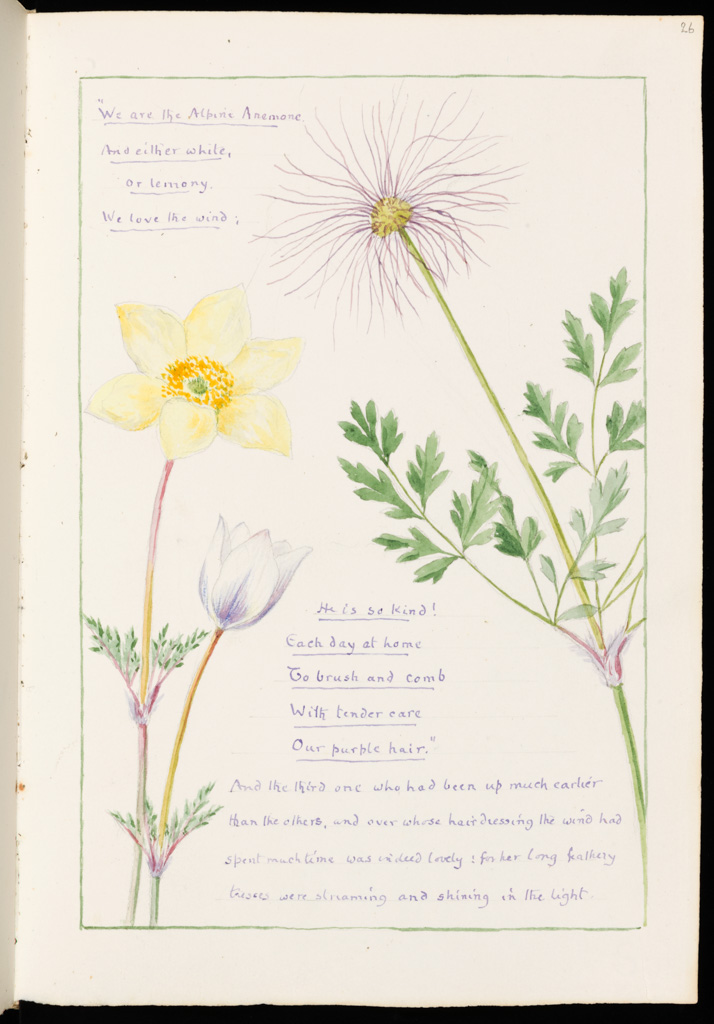

2. The Triumph of the Dandelion. This album contains a procession of the flowers of Fontanalba to celebrate the coronation of King George V in 1911; the last watercolour page, dated 1914, is an elaborate fantasy “The Triumph of the Dandelion” in which flowers compete to win “The Order of the Golden Lion”. Page by page each flower presents its claim to the prize in drawings, prose and verse. Because Clarence championed the simple wild flowers, not cultivated garden flowers, the common dandelion won the contest. In the bottom right hand corner of the final piece of the album, the stalk, leaves and flower of the dandelion are shaped into the body, legs and head of the Lion. The association in Clarence’s mind of the Dandelion (from the French “dent de lion”, lion’s tooth, because of the coarsely toothed leaves) with the Golden Lion trophy is charming. For many admirers of his work, this page is a triumph in itself.

3. Cultivated and Wild Flowers. 1911. some symmetrical patterns

4. Spring Flowers Children’s Picture-Book. 1909. Not to be confused with The Children’s Picture Book of Wild Plants of 1908 in The Bicknell Family Collection.

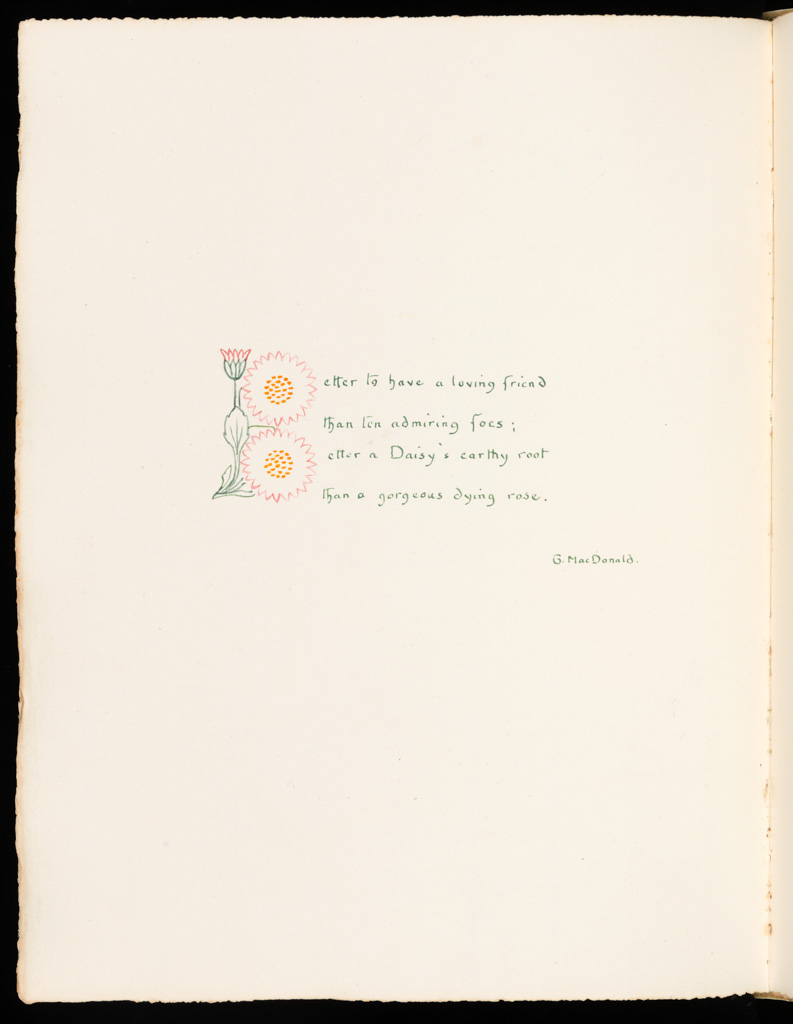

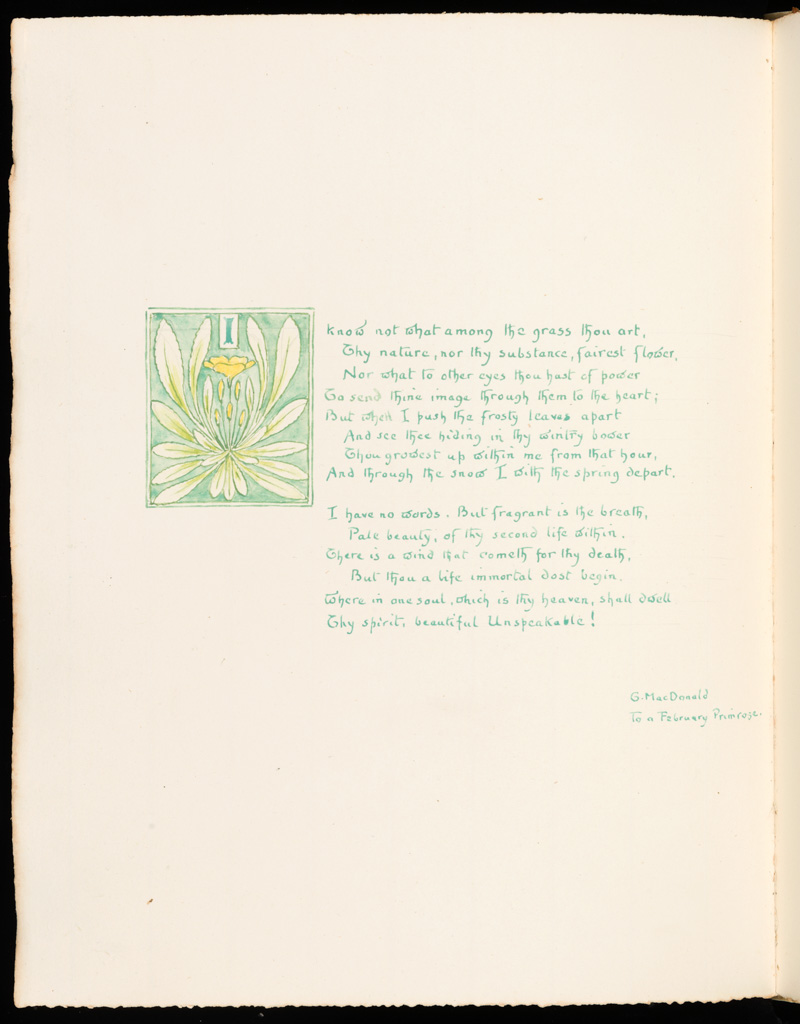

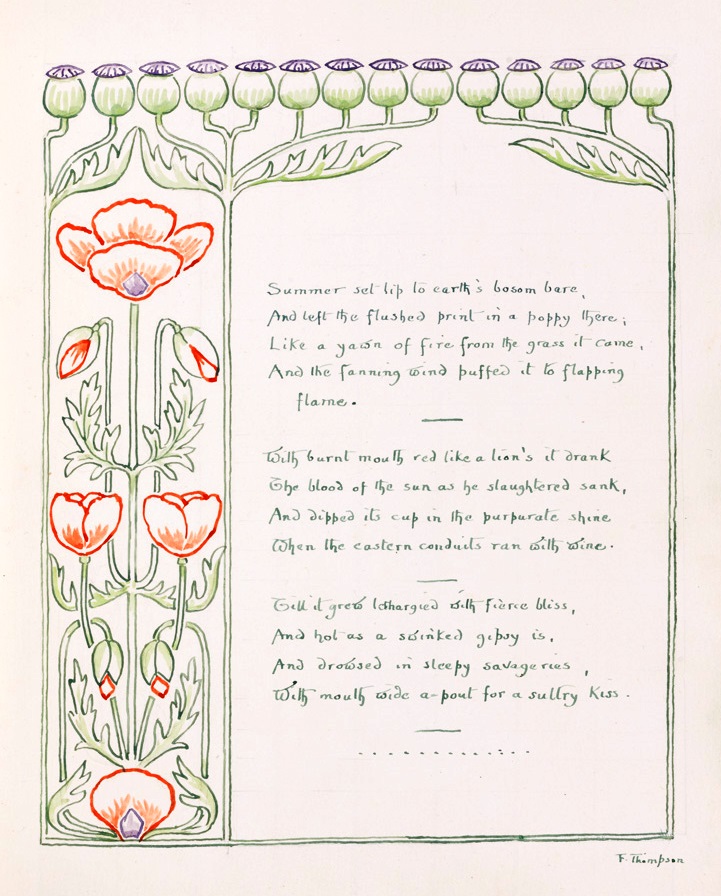

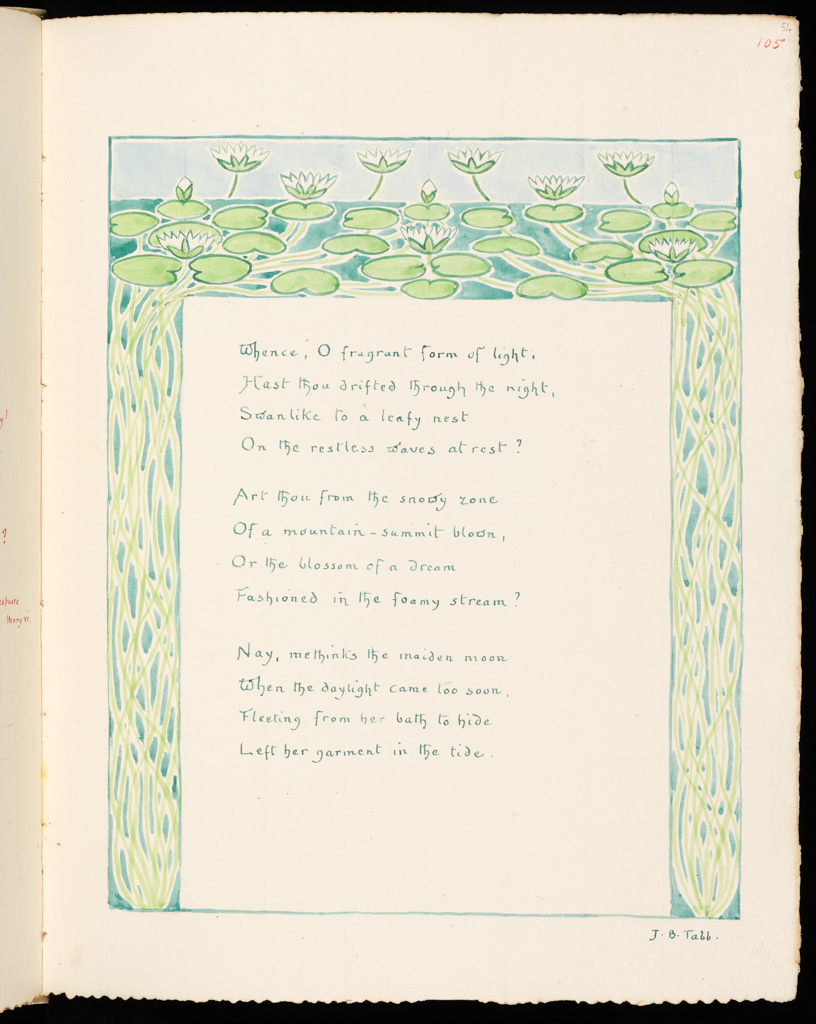

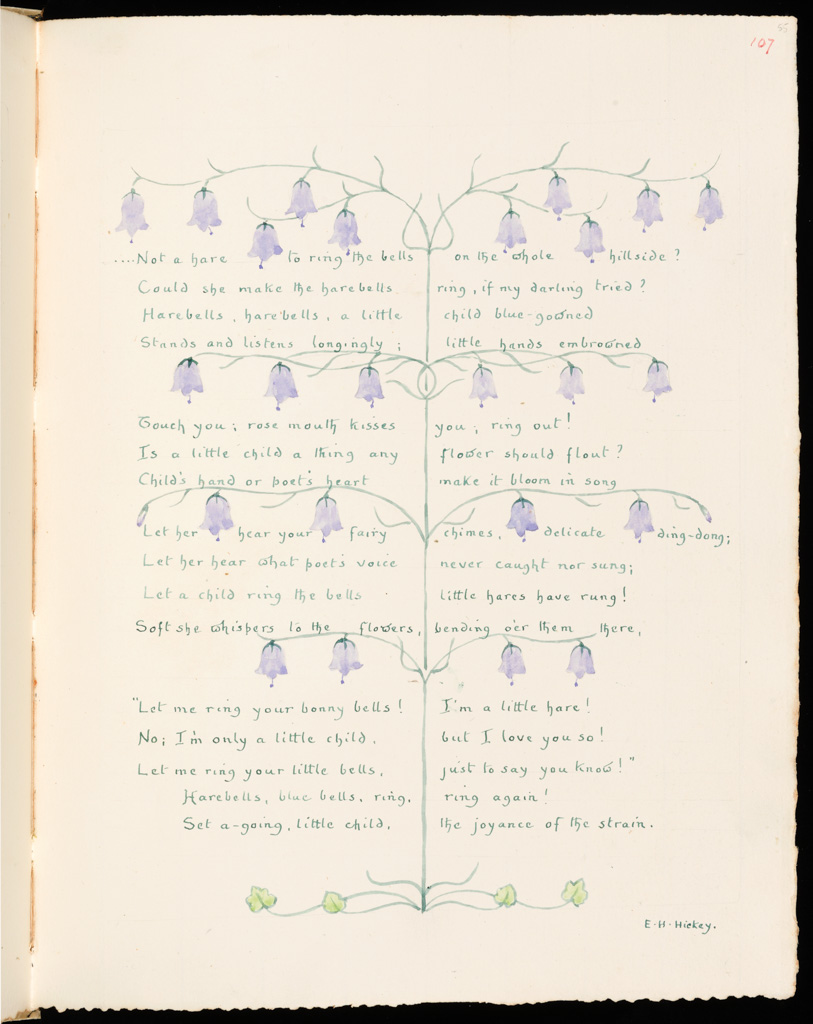

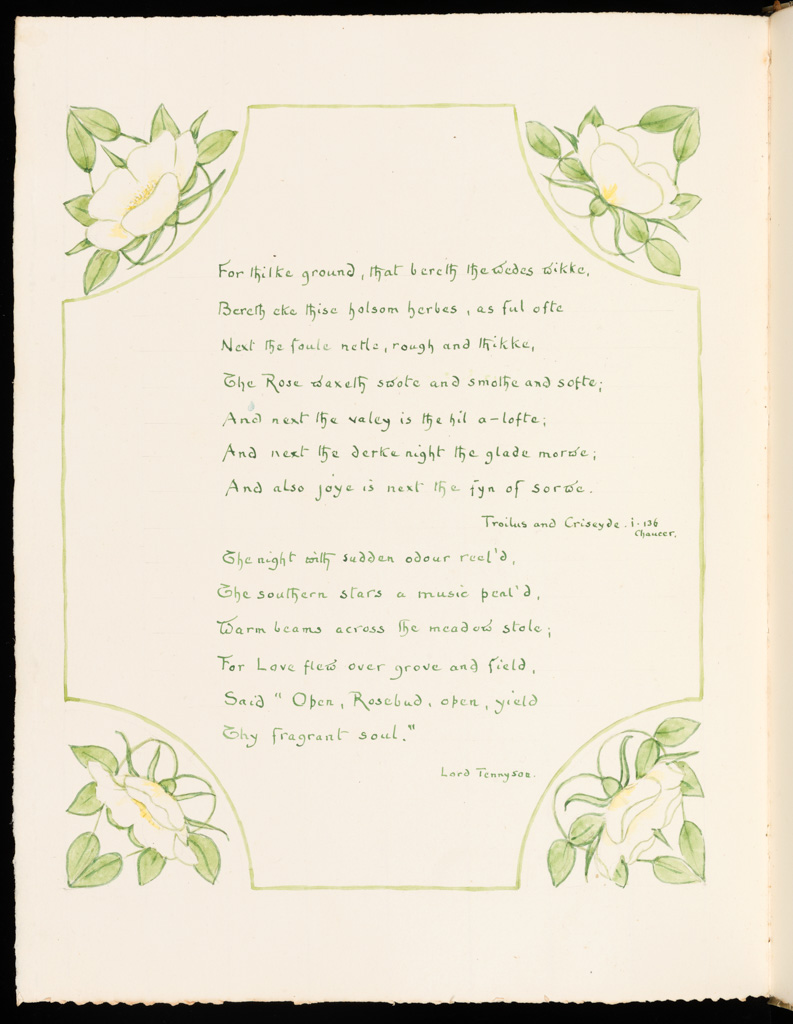

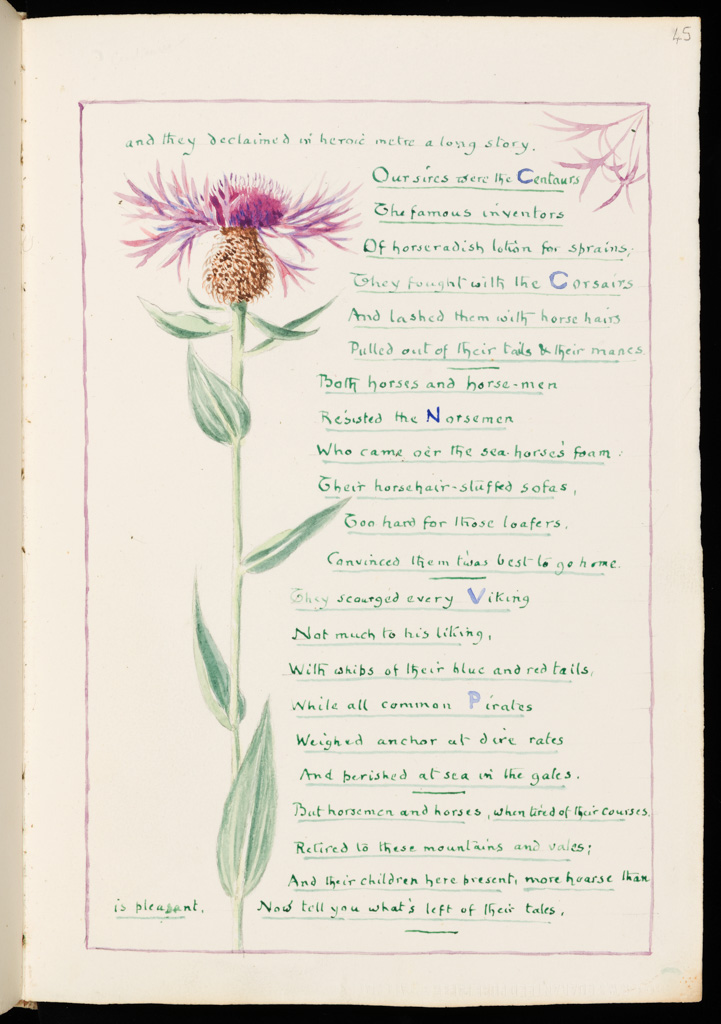

5. A Posy. 1910. Poems decorated with floral motifs and frames

6. Wild Flowers of Val Fontanalba and neighbourhood. 1908. symmetrical floral creations

7. Sketchbook. 1912. symmetrical floral creations

In a useful article in Varsity magazine Georgie Kemsley-Pein navigates the life and diverse work of an eclectic 19th Century polymath featured at the Fitzwilliam Museum exhibition of 2018.

https://www.varsity.co.uk/arts/15974

Clarence Bicknell – artist, archaeologist, botanist, ex-Trinitarian mathematician and endorser of Zamenhof’s Esperanto – is a figure who is experiencing significant reappraisal in Cambridge. Two current exhibitions mark the centenary of his death: Floral Fantasies at the Fitzwilliam Museum, and A Botanical Watercolourist at Trinity: Clarence Bicknell at the college’s Wren Library. Individuals as idiosyncratic as Clarence Bicknell encourage us to reconsider our ‘canons’ of art

As I speak with his great grandson, Marcus Bicknell, I am led around the Fitzwilliam Museum’s show, as Clarence’s work is aligned alongside paintings by Gerard van Spaendonck and Pierre-Joseph Redouté. Bicknell’s work, all in watercolour and not represented en masse, is placed around works of other European botanists, including the Victorian designs of Walter Crane: an Arts and Crafts figure who appeared to influence Clarence’s sense of decoration and colour in his book designs.

Born in Herne Hill in 1842, Clarence Bicknell was the youngest of thirteen and a bachelor his entire life. His father was a prosperous businessman, being a merchant of refined sperm oil, and an avid collector of William Turner’s watercolour drawings. After studying mathematics at Trinity in 1862 – a profession which Marcus Bicknell claims was perhaps a rebellion against his father’s strong Unitarianism – Bicknell proceeded to forsake mathematics and join the Church of England as a preacher in first Walworth and then Shropshire for the next thirteen years of adulthood. Bicknell’s botanical drawings, generated throughout his life, encapsulate polarities. The work on show at the Fitzwilliam manifests seemingly contradictory elements: both the mind of a botanist which revels in a scientifising aesthetic on the one hand, and an imaginative, enterprising streak which adheres to no such formulas.

Works such as The Triumph of the Dandelion (1914) take on this latter quality, bearing affinities to the eccentric style of Lewis Carroll, as it lauds the properties of Bicknell’s favourite wildflower. Executed in watercolour in a vellum sketchbook, it is a book which merges story-telling, poetry and painting in a manuscript-like compendium. It was also a gift to his friend, Margaret Berry, who would provide him with empty drawing albums each year from the late 1890s, which he would gradually fill and give back to her. Rhyming couplets accompany the floral motifs and, in this way, it reveals fantasy merged with a supreme interest in nature and the natural world. The Triumph of the Dandelion appears to take Crane’s Flora’s Feast and A Floral Fantasy in an Old English Garden as a starting point, merging text and illustration to construct child-like ensembles. An earlier sketchbook on display alongside The Triumph of the Dandelion is less eccentric. In the Wild Flowers of Fontanalba (1908) Bicknell moves away from stringent botanical accuracy, but drawings like Rosa Pendulina are decorative and symmetrical. Marcus and his wife Susie suggest Bicknell may have used mathematical instruments in the creation of such drawings, referring to the “kaleidoscopic effect”.

Marcus hints at some form of memory loss in Clarence, explaining why he began to abandon principles of mathematics and empiricism and began to dabble with fantasy and invention. Bicknell’s Arts and Crafts “masterpiece”, his Casa Fontanalba up in the mountains of Bordighera, symbolises such eccentricity. As the Fitzwilliam exhibition notes, Bicknell decorated and inscribed his house with drawings of flowers relevant to each room; the cook’s room, for example, was adorned with illustrations of raspberries, gooseberries, strawberries and wild spinach. Inscriptions in Esperanto also feature on the walls, and the names of all his guests who stayed were recorded by Bicknell himself over the house.

Individuals as idiosyncratic as Clarence Bicknell encourage us to reconsider our so-called ‘canons’ of art; whilst a figure on the periphery of British culture in many ways, Bicknell was massively influential in his own town in Italy. He has since had a biography, biopic and museum dedicated to him, and Bicknell-designed merchandise (wrapping paper and cards) can be found in bounty at the Fitzwilliam’s gift shop. Possessing catholic interests, as Marcus’ Bicknell’s foundation aims to reveal, Clarence followed his own philanthropic, artistic and archaeological passions, as he amalgamated elements of science and creativity – seemingly antithetical in his own life at university – to merge recreation, fantasy and empirical observation in an eclectic manner.

Read also an assessment of Clarence Bicknell by Nicholas Bell, curator of the Wren Library at the University of Cambridge… https://trinitycollegelibrarycambridge.wordpress.com/2018/06/07/a-botanical-watercolourist-at-trinity-clarence-bicknell/https://data.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/id/agent/agent-157844