In 1950, St-Tropez became famous by the arrival of movie stars. Bordighera was invented by a different charm of a different era. The foundation of the town of Bordighera dates back to 1470. The palm trees earned the town the name “the Jericho of Italy.” Its public celebrity was launched by novelist and patriot Giovanni Ruffini (1807-1881) who set his Dr. Antonio there. Published in 1855, it was translated into English the same year. It is a love story that depicts Italy in a very favorable light. In 1862, Bordighera is in the guide book – but the same book says “There is nothing that is worth a visit.” Better one should go, as Doctor Antonio did, to the hill above.

“A glorious extent of hilly coast against a background of lofty mountain, stretch semi-circularly from East to West, broken all along its length by capes and creeks, and studded with towns and villages, all of original character.” The railway arrived in 1872, followed shortly by the builders. Instead of “one small and primitive inn, there grew fine hotels. There were some hazards too. “The backs of the old village, poorly exposed but with a great view, is the Hôtel Bella vista hotel. Odors in the neighborhood … are terribly bad. “Better go to the Hôtel des Iles Britanniques!” Bordighera became as exclusively British as Nervi was German.

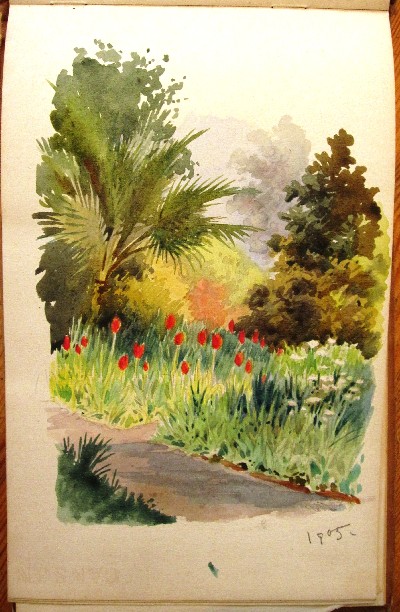

In winter the English population could reach 5,000 people in a town of 7,000 inhabitants in total. Bordighera today, although there are less palms, is a green and handsome town. It looks well, by contrast with the bare concrete of the new buildings in other resorts of the Riviera. This is how I see it now, but there was a time before these villas. At this time they appeared themselves new and ugly, disfiguring the better and yet older Bordighera. “In those days,” wrote Edward Berry in 1931, “and indeed, until thirty years ago, wild flowers grew in profusion in Bordighera, the country was unenclosed, the olive terraces were free to all-comers, while all the red and purple anemones, violets and narcissus, tulips and gladioli were within reach of us all, in the immediate vicinity of the villas and hotels.

A good climate, warm and dry, was beneficial. Those with tuberculosis and with wealth followed an annual rhythm, at St Moritz or other alpine resorts in summer and Bordighera or another resort on the Mediterranean in winter.This is one central cause why the Bordighera season was winter while today we go to the Alps in winter and to the sea in summer. A British colony needs it social amenities other than the hotels and the servants in the rental houses. Over time they created a library where they could borrow novels written in their native language in order to read their hotel; Bicknell then built a museum for the city.The English Church was another foundation due to the colony.

In 1881, the son of Ada, sister of Clarence, Edward Elhanan Berry, moved to Bordighera as a bank manager and agent for the tour operator, pioneer in the field, Thomas Cook’s. He also later became British vice-Consul. Five years later Margaret Serocold visited her family villa for the first time. And in 1897, Edward and Margaret married. In 1904 they laid the foundation stone of the Villa Monte- a photograph of the ceremony (right) sees Bicknell exceptionally wearing a bowler hat. In the years that followed, Berry became the closest friends of Clarence, involving themselves in and supporting almost all his activities. After his death, they became the custodians of what he had created including the Museo Bicknell.

In 1881, the son of Ada, sister of Clarence, Edward Elhanan Berry, moved to Bordighera as a bank manager and agent for the tour operator, pioneer in the field, Thomas Cook’s. He also later became British vice-Consul. Five years later Margaret Serocold visited her family villa for the first time. And in 1897, Edward and Margaret married. In 1904 they laid the foundation stone of the Villa Monte- a photograph of the ceremony (right) sees Bicknell exceptionally wearing a bowler hat. In the years that followed, Berry became the closest friends of Clarence, involving themselves in and supporting almost all his activities. After his death, they became the custodians of what he had created including the Museo Bicknell.

Susie Bicknell, March 2013

Museo Bicknell in Bordighera

The excellent Wikipedia page for the Museo Bicknell (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bicknell_Museum) informs us thus…

Clarence Bicknell was the first to systematically study the images engraved on the rocks of Monte Bego. During his explorations and research, he collected notes, drawings, casts, and photographs that were used by many scholars and enthusiasts. Many of his works were published in the volumes of the Linguistic Society and in French specialized magazines. Bicknell was a passionate botanist; he devoted himself to the study of the local flora and the Maritime Alps in general. His research was published in two books which became a point of reference for scholars in the field: Flowering plants and ferns of the Riviera (1885) and Flora of Bordighera and San Remo or a catalogue of the wild plants growing in western Liguria in the area bounded by the outer watersheds of the Arma and Nervia torrents (1896).

The fruits of his passion can be seen in the Bicknell Museum in Bordighera. Created in 1888, it was the first museum of western Liguria. The rectangular building has an entrance protected by a portico with four Roman-inspired columns, built by the English architect Clarence Trait. The interior is inspired by the structure used in Anglican churches, with the podium required by lecturers for their academic presentations. Both sides have a fine fireplace decorated by Bicknell with floral and animal motifs. On the fireplace on the right, there is a quote by Dante Alighieri: “Don’t do science if you do not think you have understood”, and on the left, the crests of those who collaborated in the creation of the museum: Clarence Tait, Giovenale Gastaldi, Francesco Giovannelli, and Bicknell, The museum also contains Clarence Bicknell’s library, where it is possible to consult some 85,000 volumes, 3,000 journals specialised in art and local history, 14,000 engravings, and his famous personal collection of butterflies, known to still be one of the most prestigious in Europe.

On Bicknell’s death, all the museum’s properties were inherited by the son of his sister, Edward Elhanan Berry, with whom he was very close, and by his wife Margaret Serocold Berry, whom he considered as a daughter. Berry came to Bordighera in 1880 at the age of 19 years to open a bank for the British. He immediately formed a special bond with this uncle whom he never knew before, and who passed on to him a passion for botany and history. Berry, who did much with his uncle for the creation of the museum, made many contributions to the collections gathered by Bicknell. In the building adjacent to the museum lies the International Institute of Ligurian Studies, where one can admire the original book published by Berry in 1931, At the western gate of Italy, which was long regarded as an essential text for anyone who wanted to study art and architecture of the Italian Riviera.

When Edward died, Margaret worked to maintain the museum and the cultural activities launched by Bicknell and by her husband. She even made their private residence, Villa Monteverde (via Mostaccini 54), now a private residence, one of the most fashionable lounges in Bordighera. During the Fascist period, the British became persona non grata in Italy, and Margaret passed the precious museum and all of its contents to Nino Lamboglia, with whom she had worked in 1932, to build the future International Institute of Ligurian Studies.

The Bicknell Museum, the International Institute of Ligurian Studies, and the portion of the Roman street (Via Augusta) are part of the property protected by the Superintendence for Architectural Heritage and Landscape of Liguria.

http://www.museobicknell.com/ Contact the International Institute of Ligurian Studies and the museum via the Director, Dssa. Daniela Gandolfi bicknell@istitutostudiliguri.191.it

Further reading on this web site:

Clarence Bicknell – All Saints Church Bordighera archives

by Graham Avery, original research in 2017 into the archives which are kept in London’s Metropolitan Archives, and the accompanying photos of the archives;

Clarence Bicknell – All Saints Church Bordighera archive photos

Margaret & Edward Berry by Marcus Bicknell on “Edward and Margaret Berry – Vital support for Clarence Bicknell at Bordighera and Casterino” at the Museo Bicknell on 1st June 2013.

Clarence Bicknell – George MacDonald by Susie Bicknell 2015

and other aspects of Bordighera and Riviera life and personalities on the Documents page of this web site.