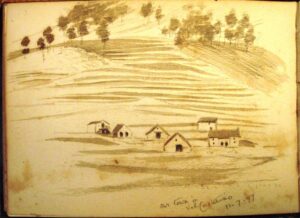

In the summer of 1886, Clarence Bicknell rented a house at Castérino on the gentler slopes of Mount Bego, where he could combine his studies of alpine plants and the rock engravings. Increasingly his summers were spent in amassing his collection of drawings, rubbings, and photographs, on which he based his first papers in Italian scientific journals. His 1897 drawing of 6 small buildings (below, right) is titled, ironically or not, “our town”. In 1902 he published in Bordighera “The Prehistoric Rock Engravings in the Italian Maritime Alps”, and a further account of his explorations followed in 1903. The unwelcome news that year, that his rented base in Castérino had been sold and that no other was available, was met with his decision to build a place of his own. All materials had to be transported by mules from Tende. Work began in 1905 and finished a year later. The plot of land was provided for Clarence’s lifetime by the Count Guido d’Alberti de la Briga whose family estate covered, and still covers, a large part of the Mercantour from La Brigue to Tende and the Vallée des Merveilles. The architect Robert MacDonald conceived a simple rectangular plan on two floors in a colonial style with terrace and balconies on three sides.

In the summer of 1886, Clarence Bicknell rented a house at Castérino on the gentler slopes of Mount Bego, where he could combine his studies of alpine plants and the rock engravings. Increasingly his summers were spent in amassing his collection of drawings, rubbings, and photographs, on which he based his first papers in Italian scientific journals. His 1897 drawing of 6 small buildings (below, right) is titled, ironically or not, “our town”. In 1902 he published in Bordighera “The Prehistoric Rock Engravings in the Italian Maritime Alps”, and a further account of his explorations followed in 1903. The unwelcome news that year, that his rented base in Castérino had been sold and that no other was available, was met with his decision to build a place of his own. All materials had to be transported by mules from Tende. Work began in 1905 and finished a year later. The plot of land was provided for Clarence’s lifetime by the Count Guido d’Alberti de la Briga whose family estate covered, and still covers, a large part of the Mercantour from La Brigue to Tende and the Vallée des Merveilles. The architect Robert MacDonald conceived a simple rectangular plan on two floors in a colonial style with terrace and balconies on three sides.

The Casa Fontanalba was built by Clarence Bicknell and his contractor Signor Lanteri of Tenda in summer 1905 and the spring of 1906 in what is now the village of Castérino. Casa Fontanalba was ready for use in June 1906 so that Bicknell could stay there for his annual visit in ‘my beloved mountain’.

The decoration of the building by Clarence Bicknell is outstanding in the detail of the execution, the coherent whole and the way in which it summarises Clarence’s life and works. Features like fireplaces and the position of beds are suitably framed and decorated. The walls of many of the rooms are framed with friezes painted in colour on the plaster, together with patterns composed of the flowers found around the house, motifs drawn from his archaeological discoveries – the rock engravings – proverbs in English and Esperanto mounted in heraldic shields and illuminated initials of his friends and visitors. A visitor wrote in his diary “By the time I got up the following day, Clarence had already painted my initials in the next available space on the wall.”

The proverbs in Esperanto feature also on the windows and doors of the house, where Clarence used oil paints. Happily, the shutters, when closed, protect the decoration from the elements; these decorations are visible when the shutters are fully opened. Only in a few cases has the painting of the shutters suffered the passage of time and the elements. The d’Alberti family has maintained the Casa Fontanalba with significant care and investment over the years; considering the mountain location and the 6-8 month long coverage by snow every year, the exterior and interior of the house are in good condition. The proximity of the stream to the North side and the melting of the snows in spring put the Casa at significant risk of dampness, so the family is obliged to find the means to ensure its condition.

Clarence Bicknell described the creation of the house and garden in a hand-written note, probably written in about 1915. The transcript of the note, which you can download here, makes interesting reading.

The splendour of Clarence’s decorations were featured with full colour photos by Jean Pierre Naudal in the magazine “World of Interiors” of June 19903 and in Christopher Chippindale’s “A High Way to Heaven”4. At the request of the d’Alberti family, pending their decisions on future funding of the maintenance of the house, we do not display here a multitude of the Naudal photos. It is not clear how the photos could be monetised, but the Clarence Bicknell Association would hope to be able to cooperate with the family in finding the means of doing so and in making images available on a suitable basis.

The Casa Fontanalba is not open to visits by the public. Because of the risk of damage to the decorations it would be necessary to have the house attended at all times. The traffic of tourists to Casterino is not big enough to hope for a regular flow of visitors, especially as most visitors are there to go walking in the Fontanalbe and the Vallée des Merveilles. Tourist interest is catered for by the excellent Musee des Merveilles at Tende http://www.museedesmerveilles.com

Download Clarence’s own description of the creation of the Casa Fontanalba

2 Robert Falconer MacDonald was spending parts of the year, from 1891 on, with his brother Greville in the Casa Coraggio in Bordighera, a house given to his father George by “a fan”. Robert had designed his father’s house St. George’s Wood in Haslemere. Tuberculosis had killed four of Robert and Greville’s siblings and the Italian climate was thought to be beneficial for George’s health and that of his children. (MacDonald, Greville, 1932, Reminiscences of a Specialist, London, George Allen and Unwin).

3 The World of Interiors, London, June 1990. Article “Vallee des Merveilles” by Marie-France Boyer with 17 colour photos by Jean-Bernard Naudin. Pages 124-135

4 “A High Way to Heaven, Clarence Bicknell and the “Vallée des Merveilles”, Conseil Général des Alpes-Maritimes, Musée Départmental des Merveilles, Tende, 1998, 79 pages. This book, published in France in three language versions (English, French, Italian) is difficult to obtain, and is not generally available in British libraries