Announcing an innovative exhibition involving Clarence Bicknell ...

CHRONOS… The AI-enhanced exhibition

THE FOOTPRINT OF MAN IN THE ANTHROPOCENE OF LIGURIA

350,000 YEARS AGO TO NOW

The exhibition is curated by Stefano Schiaparelli (Associate Professor (Zoology and Marine Biology) at the Università degli Studi di Genova) acting for the university’s Rector’s delegate for the enhancement and propagation of the university’s archives and museums. Clarence Bicknell donated to Genoa University 3,165 rock engraving copies (frottages), 10,000 pressed flowers (herbaria), 3,428 botanical water-colours and his 9 beautiful field notebooks on the rock engravings. In 2022, in order to “bring into the light” these materials (that have so far only partly been studied), thanks to the availability of funds from the Italian Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities, all the drawings, all the field notebooks and almost all of the frottages have been digitised. Now the University can share, with scholars and the public, this incredible legacy and cultural heritage. To this aim, they are launching the exhibition focusing on the transformation of the Ligurian region made by humans, from the Neolitic to the Anthropocene. Professor Schiaparelli is supported by many other members of the University including Mauro Mariotti, Professor of Environmental and Applied Botany at the University of Genoa and director of the Hanbury Botanical Gardens. The aim of these activities is to share the Genoa University’s cultural heritage and deliver information and “food for thought” to the public.

The exhibition will open on November 17, 2023 in Genoa, at the Palazzo Ducale (https://palazzoducale.genova.it/). It will remain open for a couple of months then travel to other towns in northwest Italy such as Bordighera, Vingtimiglia, San Remo, Finale etc.The rock engraving images frottages will document the development of the hunters-gatherers to agriculture, focusing on the images of plowing with ox carts. The digital images will be projected on a wall of the exhibition, introduced by Clarence Bicknell himself; advance in AI (artificial intelligence) both the moving images of Clarence Bicknell and Arturo Issel, their realistic avatars and their voices. Visitors will be enchanted by the story of their great friendship and the exchange of materials and knowledge between two great scholars that worked so passionately in Liguria in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The Università degli Studi di Genova has invited Marcus Bicknell (Clarence’s great grand nephew) and the Clarence Bicknell Association of which he is Chairman to be part of the scientific committee and a partner of the initiative, alongside the University, the Fondazione Palazzo Ducale and the Archival and Bibliographic Superintendency of Liguria. Marcus has gratefully accepted and has already started providing relevant images, texts, video footage, permissions and other information for Professor Schiaparelli.

A note about the title of the exhibition… Chronos means time. The whole exhibit revolves around the time line between the evolution of Home sapiens and today, from hunter-gatherers and farmers to the industrial and communications societies of today. The H of CHRONOS is in the form of The Sorcerer (Le Sorcier in French and Lo Stregone in Italian) – a celebrated rock engraving discovered by Bicknell in the high Alps. The two daggers and raised arms are striking symbols of man’s aggressive attitude to the environment.

A note about the key characters in the exhibition, Clarence Bicknell and Professor Arturo Issel

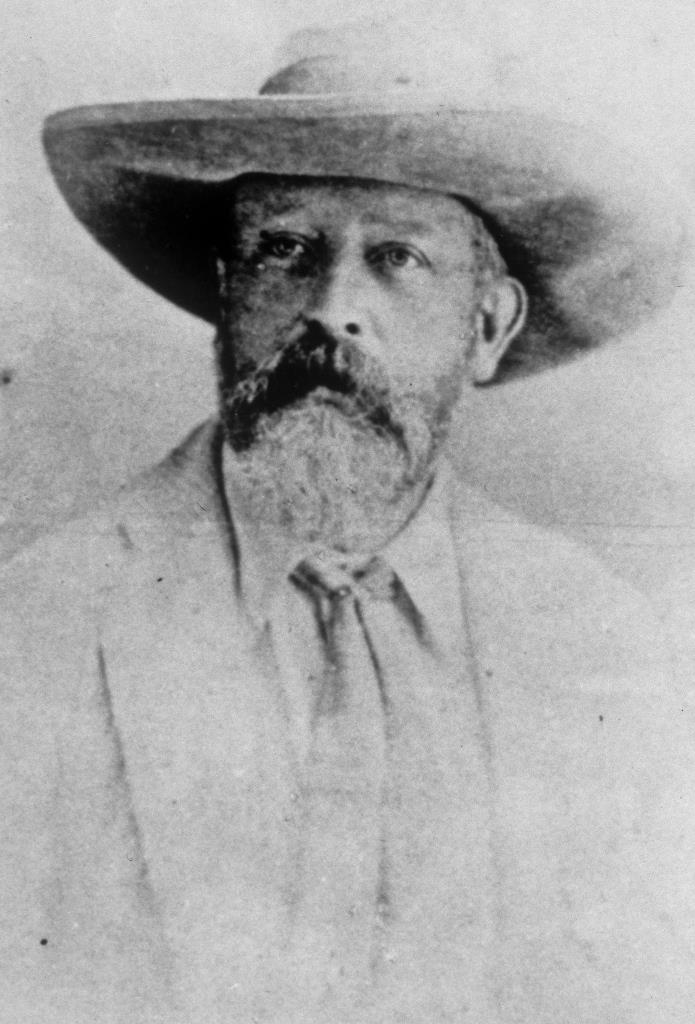

Arturo Issel (Genoa 1842 – 1922) was an Italian geologist, palaeontologist, malacologist and archaeologist, born in Genoa. He is noted for first defining the Tyrrhenian Stage in 1914. Issel was also renowned at the time for his work on codifying information within anthropology and ethnology, for which he is still remembered. Issel participated in several expeditions to East Africa, including one led by Orazio Antinori and Odoardo Beccari in 1870. He was appointed professor of Geology at the University of Genova in 1866. He maintained a close relationship and correspondence of letters with Clarence Bicknell who had located, copied, catalogued and interpreted 12,000 rock engravings in the Vallée des Merveilles on the Italian-French border. Issel and Bicknell worked together on the limestone engravings of Ciappo delle Conche at Orco Feglino near Finale Liguria.

Clarence Bicknell (1842 London -1918 Casterino) was a multifaceted British clergyman, celebrated not only for his expertise as an archaeologist but also as botanical painter, arts and crafts watercolourist, Esperantist, humanist and philanthropist. His artistic flair, combined with his deep-rooted love for nature, positioned him as a prominent figure in the realm of botanical illustration during his lifetime.Cambridge University archaeologist Christopher Chippindale writes on the Clarence Bicknell web site: “In 1909, the senior French prehistorian Cartailhac paid Bicknell a visit. He was greatly interested by his long day’s excursion into the Val Fontanalba. The rocks were much more wonderful than he had expected; and he said. “It is a great mystery.” His antiquarian colleagues had previously escaped into Carthaginian fantasies. In study of the Merviglie today, one sees emphasis on a thorough field search, on a meticulous field record and inventory, on classification, and on considered inference from studious observation in the field Clarence’s first photo of Le Sorcier and comparative analysis of the record. In short, Bicknell’s efforts make his work the model for work a century later. “Why is this so? The truth is that the then professionals had no technique to study the art, beyond what Bicknell worked out for himself. Professor Arturo Issel gave over a large portion of his large prehistory of Liguria (1903) to an account of the figures. Bicknell called this the “most important and comprehensive contribution to the subject yet written”. In comparing Bicknell’s writing with Issel’s, it is striking how strong the “amateur” is in its systematic observation on the ground. By contrast the “professional” is weak in its striking preference for unverifiable speculation as to motives, meaning and authorship. Issel – though he wrote 70 pages on the subject – had seen very few figures himself. For the most part Bicknell was disappointed when the experts did not come to his mountain; if they did, then so briefly.

The first compatriot British archaeologist to see them was Miles Burkitt, as late as 1929! But perhaps they had no need to go; Déchelette’s great Manuel d’Archéologie (1910) provides a sufficiently large and good account, entirely from Bicknell’s publications, and can date the figures securely to its Bronze Age period I.”He also writes in the journal Antiquity of January 2015: “Clarence Bicknell (1842-1918) appears in none of the histories of archaeology, but his work deserves to be remembered. His study of the bronze age rocke ngravings of Mont Bégo, in the Maritime Alps above Bordighera, was the first adequate work on an Alpine rock-art tradition, and the forerunner of the astonishing discoveries over the last 30 years in Valcamonica (Anati, 1961; 1980), at Sion (Gallay, 1972) and now in the Aosta valley (Daniel, 1983). Bicknell’s life and work, beyond its intrinsic interest, is an illuminating case-study in the history of the discipline, during that crucial late 19th century period when antiquarianism was everywhere giving way to the new science-based archaeology.”