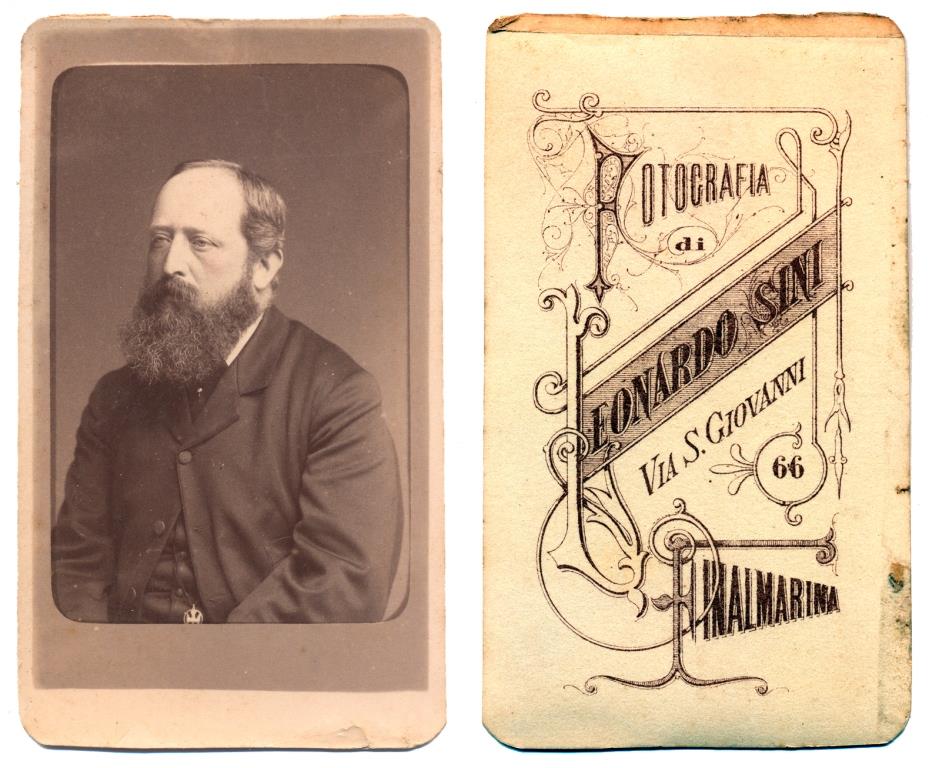

I received today a copy of an interesting photo of Clarence Bicknell. It was sent by Dr. Andrea De Pascale, PhD, Conservatore del Museo Archeologico del Finale, Istituto Internazionale di Studi Liguri (IISL), a sister museum of the Museo Bicknell. Andrea’s contact details are at the bottom of this page. The photo was acquired by the IISL as part of the “Lotto 2017” and was displayed in their 2018 exhibition. Andrea asked me for my comments on it which I was pleased to give and which I reproduce here for the interest of other academicians and followers.

1) Age and date

The photo of Clarence is clearly that of quite a young man. The sun of the mountains has not bleached his eyes. He has only a few white hairs in his beard. All this suggests that Clarence had arrived recently in the Bordighera/northwest Italy area, or in this case Finale/Finalmarina (See MARVELS – The LIfe of Clarence Bicknell page 53). We know from the photographer’s logo on the back that the photo was taken in Finalmarina. He was there twice that we know of, 1883 and 1897. That the photo is of a younger man, we can be certain the photo was taken in 1883.

2) Dressed to impress

I also note that he is wearing a tie-pin and has brushed his hair. The main objective of his trip there was the excavation with Issel, but it was also in 1883 in Finalmarina that he spent time with Alice Campbell, his lady friend who has never been identified (see https://clarencebicknell.com/wp-content/uploads/alice_campbell.pdf). Clarence wrote in 1897 to Prof Arturo Issel (University of Genoa, Archaeology) about lunch back in the winter of 1883 with “a lady” in Finalmarina. Clarence notoriously did not care about his appearance but in this photo he definitely cares! He would not care about Issel or about archaeologist, but he clearly did care about Alice. We can speculate that this smart look was (maybe unconsciously) to impress his lady friend.

3) Societas Sancti Spiritus

On a cord attached to a button of his waistcoat Clarence is wearing the silver insignia of the Societas Sancti Spiritus. You can see it in the margin of the bottom of the photo. This religious order, also named The Brotherhood of the Holy Spirit, was of great significance to Clarence; even though he had given up being a priest in 1880 he was still wearing the insignia three years later. Alice could be the reason; maybe she was present at the seminaries at Broadlands where the theology of this group was so actively discussed and which in the end brought George MacDonald to Bordighera. I can point you to the description of the Societas Sancti Spiritus by Valerie Lester in MARVELS pages 24-26 and to page 57, shown below. We know nothing certain of Alice’s thoughts on religion, but maybe the presence of the insignia on his coat is revealing. The insignia itself is in the Bicknell family collection and has been displayed by Daniela over the last three years, I know not where exactly, and I attach a photo.

Dr. Andrea De Pascale, PhD Conservatore del Museo Archeologico del Finale, Istituto Internazionale di Studi Liguri, Chiostri di Santa Caterina, 17024 Finale Ligure, Borgo SV (Italy) tel. 0039 019 690020 – fax 0039 019 681022 depascale@museoarcheofinale.it

Excerpts from MARVELS – The Life of Clarence Bicknell by Valerie Lester 2018. Societas Sancti Spiritus or Brotherhood of the Holy Spirit. pages 24-26:

Clarence had fallen under the spell of the Rev. Rowland Corbet, a mere three years older than himself, who had preceded him at Trinity. After graduating from Cambridge with a degree in theology, Corbet became a fellow of St John’s College, Oxford, where he was exposed to the leading lights of the Oxford Movement. A particular influence on him was the Rev. Richard Meux Benson, founder of the Society of Saint John the Evangelist. Corbet’s father, Richard Corbet, was lord of the manor in the parish of St Peter’s, Stoke-upon-Tern in Shropshire, and in 1869 he nominated his son as rector of St Peter’s. The move to Shropshire offered Rowland an opportunity to construct a church because the original medieval building had burned down. Using the family’s considerable funds, he set about rebuilding the church, but first erected a school that could be used on Sundays as a chapel of ease (a church building used for services, primarily for the convenience of those who cannot reach their parish church without difficulty) until the church itself was ready for services.46 At the same time, Corbet founded his own religious community, the Societas Sancti Spiritus or Brotherhood of the Holy Spirit, closely based on Benson’s community. He drew to it like-minded priests desiring a return to the early Church within a close community of brothers, and sought and gained the benediction of Pope Pius IX for his new brotherhood, on condition that the brothers say the canonical hours together.47 It is a great shame that the society’s book of rules has been lost as it would have revealed the order for each day and what tasks the brothers fulfilled. Meanwhile, back in Walworth, John Going was increasingly exhausted by the demands of his enormous urban parish and by opposition to his work; his curates were worn out too. When Clarence received the invitation to join Corbet’s brotherhood at Stoke-upon-Tern, he leapt at the opportunity to lead a religious life in the countryside, along with a chance to indulge himself in another of his passions: botany. He signed the baptismal registry at St Paul’s for the last time on 31 August 1873, and made his way to Stoke-upon-Tern, arriving there at a point when the rebuilding of St Peter’s was nearing completion. He signed the parish’s baptismal register there for the first time on 2 November 1873. What a change of scene Clarence experienced! While St Paul’s had operated in a noisy, over-populated parish, rattling with the sounds of carriages and trains, resonant with the cries of hawkers, prey to diseases like cholera and smallpox, and often smothered in London’s smoke and fog, St Peter’s, with its nine hundred parishioners, was set in the middle of nowhere, beside a stream, surrounded by green fields, sweet with the scent of flowers in the fresh air, chirping with birdsong, and now buzzing with the effort of building the church. The villagers pitched in, providing time and energy. The most useful of them all was Tom Dutton, the Shropshire Giant, whose extraordinary height, strength, and skill as a mason enabled him to place the heavy stones used in building the church tower.48 Tom was seven foot three inches tall and weighed 23 stone. He spent some time as a soldier and he also worked in a travelling circus, playing the part of ‘The British Soldier Giant.’ As St Peter’s gradually rose from the ashes of the previous church and revealed itself in its neo-Gothic glory, Clarence began to feel at home. The church, with its two naves, and a chapel next to the presbytery, was built in the same style as St Paul’s. Charles Eames Kempe – the same artist who had made the windows at St Paul’s, Walworth, and was much in demand by this time – created a stained-glass window for St Peter’s. Corbet also installed a magnificent Grindley and Foster organ and a tall and ornate font. The main difference between the two churches was scale. St Peter’s was smaller and featured a sturdy square tower instead of St Paul’s tall and elegant spire. All the same, it was a large church in a small parish. For the church’s construction, the masons used local pink sandstone, quarried at Stoke Grange Woods. Inside, Corbet installed the monumental Elizabethan tomb of Sir Reginald and Lady Corbet, recovered from the remains of the medieval church. He placed it at the front of the south nave, not far from the altar, thus acknowledging the Corbets’ status in the parish and proclaiming his own fine breeding. Four large steps led up to the altar, whose scale was somewhat at odds with the church’s dimensions. He designated two pairs of wooden benches for the brotherhood, setting them in the choir facing the altar, and built a vestibule with a door through which the brothers could enter and leave. A bell, hung above the doorway, was rung to call the brothers from the parish house to the church for services and prayers. During Clarence’s time at Stoke-upon-Tern, the brotherhood consisted of twelve men, either priests or laymen preparing for the priesthood. They were referred to as missioner priests and they lived in an open community, as opposed to a closed monastery. The group of twelve was astonishingly well-educated: four, including Clarence and Rowland Corbet, were Cambridge graduates; five were Oxford graduates; and the others were products of Lichfield Theological College. They lived in a one-storey building with a cloister just east of the parish house. The parish house itself was spacious enough to host conferences and retreats attended by theologians, priests and interested participants who arrived from all over the country – and even from abroad. The stables and carriage houses were located on the south side of the parish house, with a forge close by, much used owing to the frequent missionary journeys the brothers undertook on horseback or in horse-drawn carriages. Clarence himself went on missions to Edinburgh in 1874 and 1875 to found a temperance society on the lines of Stoke-upon-Tern’s.49 Even without the book of rules for the Societas Sancti Spiritus, it is possible to imagine how the brothers spent their time. The little bell over the presbytery door would call them to ‘hours’ several times a day. They performed baptisms, marriages and burials; they listened to confessions; they went on preaching missions to surrounding towns and villages; they grew vegetables and raised farm animals. In St Peter’s church today hangs a marvellous old print of a band of brothers fishing, etched by Henry Slocombe from a painting by W. Denby Sadler. These are generic brothers, clearly not members of Corbet’s brotherhood, but the fact that the image hangs in St Peter’s is a clue to one way in which some of Corbet’s men used their time: fishing, and thus providing food for the community. However, Clarence, who would later become an animal rights activist, might have preferred to head off into the fields and by-ways, botanising and sketching to his heart’s content.